Top 10 Hacking Devices for Ethical Hackers in 2026

February 6, 2026

21 min read

Introduction: Why Hacking Devices Are Trending

We’ve all seen the headlines: a missed patch, a brittle dependency, one bad line of code, and suddenly a company’s services go dark. Apps stop responding, users get locked out, data leaks, and what felt abstract becomes painfully real for customers, developers, and leadership alike.

But here’s what doesn’t always make the news.

While everyone is watching software failures, a quieter risk keeps growing in the background: hardware and device ecosystems. Research suggests that roughly one in three data breaches now involves IoT or other connected devices, from smart sensors to Wi-Fi cameras. In other words, hardware-related weaknesses are increasingly becoming a major attack vector 1.

Expansion of Wireless, IoT, and Physical Attack Surfaces

Today, smart devices are everywhere, quietly sending and receiving wireless signals all around us. Wi-Fi routers, Bluetooth speakers, smart TVs, car key fobs, and CCTV systems “talk” to each other 24/7. And every time a device connects, disconnects, or pairs, a wireless exchange happens in the background, creating new opportunities for attackers.

That always-on connectivity is one reason hardware pentesting tools have become so popular. Risk no longer lives only inside software. Many real-world compromises start over the air, via radio protocols and weak device configurations, in ways most people never notice until something goes wrong.

What are Hacking Devices?

A hacking device is a physical tool used to test, demonstrate, or simulate real-world security weaknesses in systems such as networks, access controls, and connected hardware. Unlike software tools that run in a terminal, these devices interact directly with cables, ports, and wireless signals.

Many of them look like ordinary USB drives, Wi-Fi adapters, or small circuit boards. In authorized penetration tests, they help teams validate whether an attacker could gain access in the physical world, before a real intruder tries. If software tools probe applications, hardware tools probe the edges where the digital world meets reality.

How Ethical Hackers Use Hacking Devices

When people hear the phrase “hacking device,” they often assume it’s meant for harm or illegal break-ins. In practice, these tools are frequently used for authorized security testing to prove a point with something tangible.

For example, a consultant might demonstrate how easily an office access badge could be cloned if the system relies on weak RFID technology. A red team might show how a rogue Wi-Fi network could lure employees into connecting and exposing credentials. Done with permission and clear scope, these exercises help organizations identify weaknesses and fix them before they turn into real incidents. In the next section, we’ll walk through common devices and the legitimate use cases they’re designed for.

Hardware vs Software Hacking Tools

The title is fairly self-explanatory, so let’s focus on what really sets these tools apart: their real-world use cases and the kinds of security problems they’re designed to test.

| Software Security Tools | Hardware Hacking Devices |

|---|---|

| Run on laptops or desktops | Are physical gadgets you can hold |

| Scan websites, servers, and apps | Interact with Wi-Fi, USB, RFID, Bluetooth, and radio signals |

| Look for bugs in code | Exploit trust in hardware and human behavior |

| Focus on digital systems | Focus on real-world access points |

| Blocked by firewalls and security software | Often bypass traditional security tools |

| Need network access | Often need only physical proximity |

Are Hacking Devices Legal?

This question comes up a lot, especially for beginners, because the answer depends on context. In many countries, owning hardware pentesting tools is generally legal. Problems start when you use them without permission.

If you’re testing your own systems, working under a signed penetration test agreement, or participating in an authorized red team engagement, these devices can be legitimate parts of the job. Using them against networks, devices, or facilities you don’t own and don’t have explicit consent to assess can get you into serious trouble. The hardware doesn’t change, but your authorization and intent do.

Ethical hacking boundaries

Ethical hackers follow strict boundaries, whether they’re using hardware tools or software. The rules are the same: you should never run any kind of security test unless you have all of the following in place:

- Written permission.

- Clear scope.

- Approved targets.

- Full reporting after the test.

If it’s not written down and approved, it’s off the limits for sure.

Top 10 Trending Hacking Devices

1. Flipper Zero

Flipper Zero Is One of the Most Talked-About Hacking Devices

If you’ve been following security content lately, you’ve probably come across this device. It shows up everywhere: conference demos, red team kits, research blogs, and even mainstream news, and that’s no accident. It bundles multiple capabilities into one portable platform, combining wireless protocols, RFID/NFC, infrared, and basic hardware interfacing instead of focusing on a single surface.

How Flipper Zero Works:

- The Flipper Zero: Your Pocket-Sized Hacking Tool

Flipper Zero is designed to capture and interact with the signals devices use to communicate. It works by observing and analyzing wireless protocols and basic hardware-level interactions. As shown in the image, it’s also surprisingly user-friendly, which is one reason it became so popular in security circles. The main menu provides quick access to core features such as Sub-GHz, RFID, and NFC.

- Reading and Cloning an RFID Card

One of the most commonly used features of Flipper Zero is its ability to read RFID cards. With a compatible card and within close range, you can scan an RFID badge by holding it near the device, which captures the card’s identifier via short-range radio communication. RFID access systems are widely used for building entry in offices, apartments, and hotels.

- Interacting With Infrared Devices in Real Time

This can be a fun, beginner-friendly way to understand how the device works. Point Flipper Zero at a TV, press a button, and you’ll see an immediate response: the volume changes, the menu opens, the screen reacts. It’s a simple demonstration of infrared control, where the device sends IR commands that many consumer electronics still recognize.

Real-World Use Case: The Great iPhone “Crash” Attack (2023)

In 2023, Flipper Zero was reportedly used in a real-world incident that caused iPhones to crash. According to Malwarebytes, a security researcher Jeroen van der Ham noticed his iPhone repeatedly crashing while travelling on a train. The phone kept displaying Bluetooth pairing requests and then rebooting. This happened because someone nearby was using a Flipper Zero to spam Bluetooth pairing requests. This impacted iPhones running iOS 17 2.

2. USB Rubber Ducky

At first glance, it looks like an ordinary USB flash drive. But this tiny gadget is a keystroke-injection tool. When you plug it in, the computer doesn’t recognize it as storage. Instead, it identifies it as a keyboard and “accepts” input as if a real person were typing at extreme speed. Because the system treats the activity as normal human input, many traditional security controls that focus on files and executables may not catch it right away.

How Rubber Ducky Works:

- The Brains of the Operation

From the outside, it still looks like a regular flash drive, but inside it contains a small processor and a microSD card slot, as you can see in the image. The microSD card stores payload scripts that tell the device what to “type” after it’s plugged in. You don’t have to be an expert programmer to create a Ducky payload: the scripting language is intentionally simple and reads more like a set of step-by-step instructions. For example, a payload can look like this:

- “Wait 2 seconds".

- “Press Windows key”.

- “Type this sentence”.

- “Press Enter”.

- The Innocent Deployment

Once a Rubber Ducky is plugged in, the sequence can execute in seconds. The computer recognizes it as a Human Interface Device (HID), specifically a keyboard, and then processes the preloaded DuckyScript as if a user were typing. In many environments, no driver prompts appear because operating systems are built to accept keyboards by default and immediately.

This is often discussed in the context of social engineering and physical security testing: unattended laptops, unlocked screens, and implicit trust in unknown USB devices can create an easy opening for abuse.

- Not Just for Laptops: Mobile Attacks

Rubber Ducky isn’t limited to Windows or macOS. It can also be used with mobile devices via a simple USB-C or OTG adapter. As shown here, the device is connected to an Android phone and sends input directly into a terminal window.

That said, the risk depends on the phone’s configuration and how it handles external keyboards and connected accessories. If a device automatically accepts keyboard input while sensitive apps are open or unlocked, it may be exposed to this kind of keystroke-injection scenario.

Real-World Use Case: The FIN7 “BadUSB” Gift Card Attack

- The “Best Buy” Gift Card Scam (FIN7 Group)

This is one of the clearest real-world examples of how dangerous USB-based attacks can be. A cybercrime group called FIN7 reportedly mailed USB devices to employees at hotels and restaurants across the US. The packages included a fake Best Buy gift card and a note instructing recipients to plug in the USB to view “product details.” Once connected, the attackers were able to gain remote access to internal systems and steal payment card data from affected organizations. While the reports did not name a specific tool like the Rubber Ducky, the devices used in the campaign behaved like HID keystroke-injection tools, the same attack class demonstrated by devices such as the Rubber Ducky 3.

3. WiFi Pineapple Mark VII

This device takes advantage of a common habit: people connecting to “free Wi-Fi.” Just because a network has a familiar name doesn’t mean it’s safe. The WiFi Pineapple is often used in man-in-the-middle (MitM) style security tests, where the goal is to show how traffic can be intercepted when users connect to the wrong access point.

It can automate a well-known technique called an “Evil Twin” attack. Rather than cracking a secured network, the idea is to imitate a trusted Wi-Fi name and trick nearby devices into connecting to the attacker-controlled hotspot. That’s why this scenario is most common in public spaces such as cafés, restaurants, and airports.

How WiFi Pineapple Works:

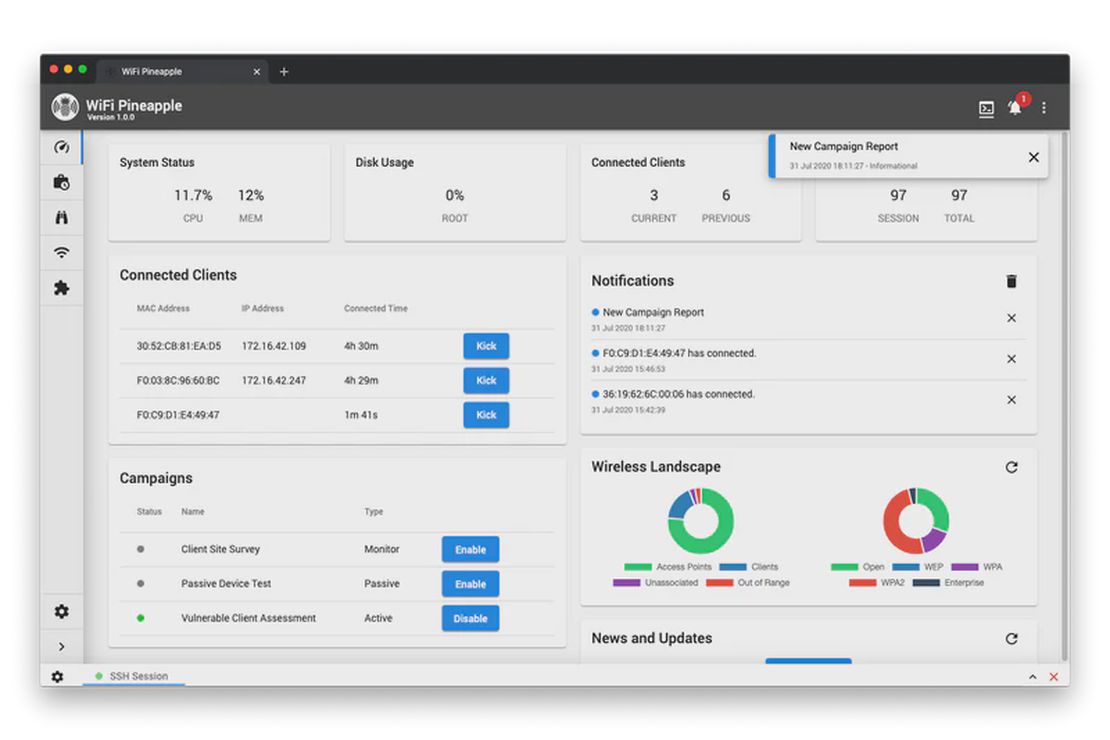

- The “PineAP” Dashboard: Seeing the Invisible

Unlike Rubber Ducky or Flipper Zero, this device is closely tied to a companion software suite called PineAP. It looks like a typical Wi-Fi router dashboard, but it goes well beyond basic configuration. As shown in the screenshot, PineAP can display nearby devices and access points in real time, including the network names some devices are actively searching for. In an authorized test, that visibility helps a tester understand when a nearby device is trying to reconnect to something like Corporate_Guest_WiFi, even if that network isn’t actually present.

- The “Evil Twin” Trap

This is where the “Evil Twin” trap comes in. The Pineapple can mimic the name (SSID) of a legitimate network, such as “Starbucks Free Wi-Fi” or “Airport_Lounge,” and broadcast it with a stronger signal than nearby access points. If a device is configured to auto-join known networks, it may connect to the strongest signal it recognizes.

At that point, the risk is that the user believes they’re on the real network, but they’re actually connected to the tester’s access point. Depending on how the connection is set up and what protections are in place (HTTPS, VPN, certificate warnings, etc.), traffic may be exposed to monitoring or manipulation during an authorized security assessment.

- The “Captive Portal” Heist

Once the victim connects, the device can present a captive portal, the kind of pop-up login page you’ve likely seen in hotels, hospitals, or dorms. In a malicious scenario, an attacker could clone a familiar-looking portal and prompt the user to “sign in” to get online. If someone enters credentials on that fake page, the information can be captured and forwarded to the attacker’s dashboard.

Case Study:

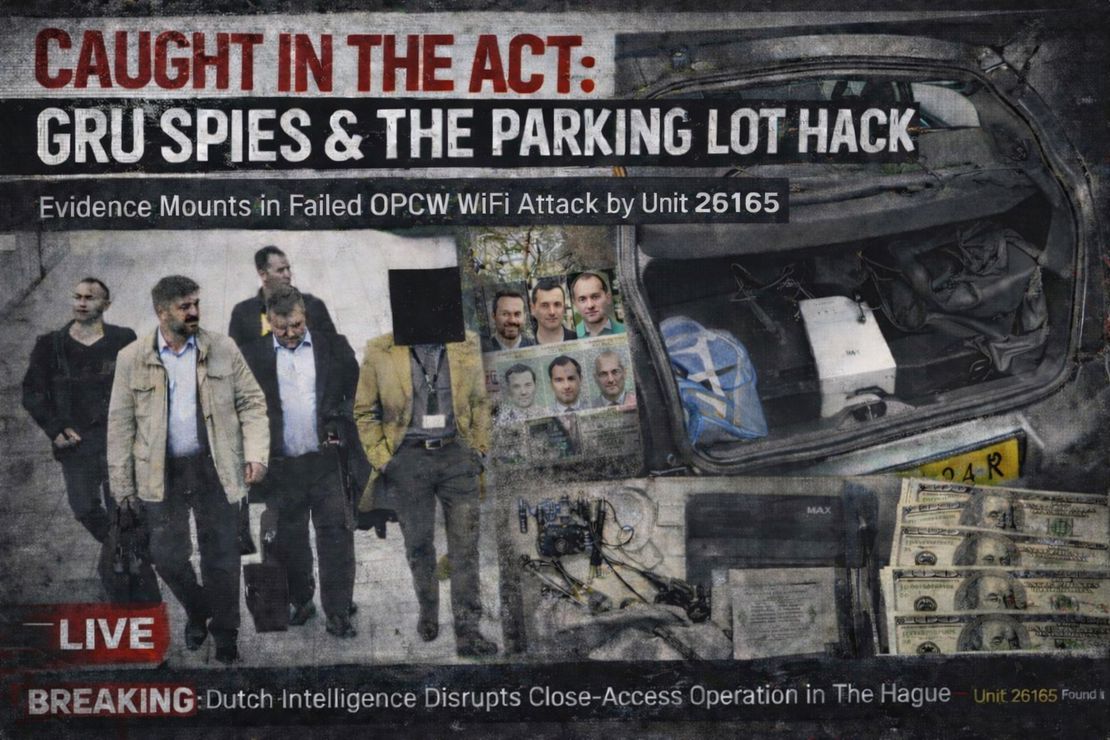

- The Russian Spies in the Parking Lot (Operation w/ Unit 26165)

In 2018, four Russian GRU officers from Unit 26165 were caught by Dutch intelligence while attempting to target the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) in The Hague. Instead of attacking remotely, they reportedly chose a close-range approach, parking near the building with a vehicle loaded with Wi-Fi interception equipment, including devices similar in concept to a Wi-Fi Pineapple. The goal was to lure nearby laptops into connecting to a rogue “evil twin” network and capture login credentials. The operation failed, but it’s a sharp reminder that even high-security organizations can be exposed by an attacker operating from nearby with the right wireless tools 4.

Seeing is Believing

See how Netlas can elevate your threat analysis. Book a quick demo with our team.

4. Bash Bunny

This isn’t just another USB stick that looks like a Rubber Ducky. It works differently. Instead of presenting itself only as a flash drive or a keyboard, it can dynamically change how it identifies to the target system. Depending on the scenario, it may behave like a network adapter, a storage device, or another type of USB peripheral.

How Bash Bunny Works:

- The Brains of the Bunny

Bash Bunny is essentially a tiny Linux computer with its own processor, storage, and operating system. Instead of running simple keystroke scripts, it can execute payloads and automation that control how it behaves the moment it’s plugged in. Unlike a Rubber Ducky, these payloads typically require little to no user interaction. The device can present itself as whatever the target system is most likely to trust in that moment, such as a keyboard, a network adapter, or a USB drive.

2. The Silent Deployment

The moment a Bash Bunny is connected, many systems will treat it as a trusted peripheral. Operating systems are designed to work seamlessly with common accessories like docking stations, Ethernet adapters, and USB hubs, so network hardware is often accepted with minimal friction.

When configured to act as a USB network adapter (USB-NIC/Ethernet mode), it can insert itself into the connection path in a way that enables man-in-the-middle style testing. In that position, traffic may pass through the device first, allowing an authorized tester to observe routing and validate whether communications can be intercepted or redirected in that environment.

Case Study: The “DarkVishnya” Bank Heists

DarkVishnya, a cybercrime group, carried out a series of highly targeted attacks against banks in Eastern Europe. The attackers reportedly entered bank branches while posing as customers or job applicants. Once inside, they connected malicious USB devices to internal workstations. While investigators did not name the exact hardware used, according to Kaspersky’s report the tradecraft aligns with the kinds of scenarios tools like the Bash Bunny are designed to simulate in security testing today 5.

5. Proxmark3 RDV4

If Flipper Zero is a Swiss Army knife for casual exploration, Proxmark3 RDV4 is more like a full lab bench.

While Flipper Zero typically focuses on reading and emulating basic card data, Proxmark3 RDV4 is built for deeper RFID/NFC research. It can capture and analyze the exchange between a card and a reader, helping you understand what’s happening at the protocol level. Depending on the card technology and configuration, it can also support advanced analysis and emulation workflows across many badge types.

How Proxmark3 Works:

1. The Dual-Antenna Powerhouse

Proxmark3 stands out because it supports both major RFID “families”: low frequency (LF) and high frequency (HF). Many readers and hobby tools focus on just one band, but Proxmark3 includes dedicated hardware for both, with separate antennas on the board.

In general terms, LF (around 125 kHz) is common for older proximity badges, while HF (13.56 MHz) is used by many contactless smart cards and NFC-based systems, including some access badges and transit/payment-style technologies. Compared to simpler tools, this means you don’t have to guess the frequency first. Proxmark3 is built to handle both and let you investigate what technology a card is using as part of the workflow.

2. The Silent Sniffer & Replay

This is where things get interesting: in some scenarios, you don’t necessarily need to handle the victim’s card. By placing Proxmark3 near the interaction between a card and a reader, it can be used to sniff the exchange, capturing the back-and-forth messages the two devices send to each other.

In an authorized assessment, this helps you evaluate whether an access system is vulnerable to replay-style attacks. If the protocol lacks proper anti-replay protections (for example, strong mutual authentication and fresh session values), a recorded exchange may be reusable, which is exactly the kind of risk this testing is meant to uncover.

3. Cracking the Encryption

Cracking encryption is very different from reading a simple card ID. Many modern cards, such as MIFARE DESFire or iClass, use strong cryptography, so a simple “copy” won’t work. Proxmark3 can connect to a computer and support more advanced analysis and testing workflows. In authorized research and pentesting, it may be used to evaluate whether a deployment is relying on weak configurations, recoverable keys, or known, well-documented issues in specific card technologies.

Case Study: The Master Key Hotel Hack

Two security researchers from F-Secure, Tomi Tuominen and Timo Hirvonen, uncovered a serious weakness in a hotel keycard system by analyzing a single expired room key with a Proxmark. By reverse-engineering the card data, they identified a flaw in the cryptography used to generate keys, which enabled them to create a “master key” that could open rooms in affected hotels. Reports estimated the exposure at a global scale, potentially impacting tens of thousands of hotels across many countries 6 7.

6. HackRF One

Most consumer radios are built for specific jobs: your car stereo receives FM, and your phone talks to a cellular network. Their hardware and firmware are largely locked to those bands and protocols. HackRF One is different because it’s a Software Defined Radio (SDR), meaning much of its behavior is controlled in software rather than fixed hardware.

In practice, that makes it extremely flexible. It can tune across a wide range of frequencies, roughly from 1 MHz up to 6 GHz, which covers many real-world signals used by common devices and systems, from garage door remotes and sensors to parts of aviation and GPS-related bands.

How HackRF One Works:

1. The “Replay Attack” (Car Unlock)

One classic SDR scenario involves older systems that rely on fixed codes. Some legacy devices, such as certain garage door openers, apartment gates, and wireless doorbells, listen for a specific radio code and accept the same code every time.

In that context, an SDR like HackRF One can be used to capture the transmission and later replay it. In an authorized test, this is used to evaluate whether a system is vulnerable to replay attacks and to justify upgrades to rolling-code remotes, modern encryption, or other anti-replay protections.

2. GPS Spoofing (Faking Location)

This is where HackRF One goes beyond passive listening and becomes an active transmitter in a controlled research setting. In close-range demonstrations, researchers have shown that a device can be fed a simulated GPS signal strong enough to compete with real satellite data, causing nearby receivers to calculate an incorrect position. In examples like the one shown, a phone’s location can “jump” to places it’s never been because it trusts the stronger signal. This technique, known as GPS spoofing, is typically discussed in the context of lab tests and security research, including evaluations of resilience in drones and tracking systems.

Real-World GPS Spoofing Incident: Ships “Teleported” Inland

In 2017, captains of more than 20 commercial ships sailing in the Black Sea noticed their GPS receivers suddenly reporting an impossible location: Gelendzhik Airport, more than 30 kilometers inland. The crews could see open water around them, yet the navigation systems insisted they were sitting on a runway. Later reporting and analysis suggested the incident was linked to large-scale GPS spoofing activity in the region, widely attributed to Russian electronic warfare capabilities. While devices like the HackRF One were not involved, the event remains a widely cited real-world example of GPS spoofing at scale 8.

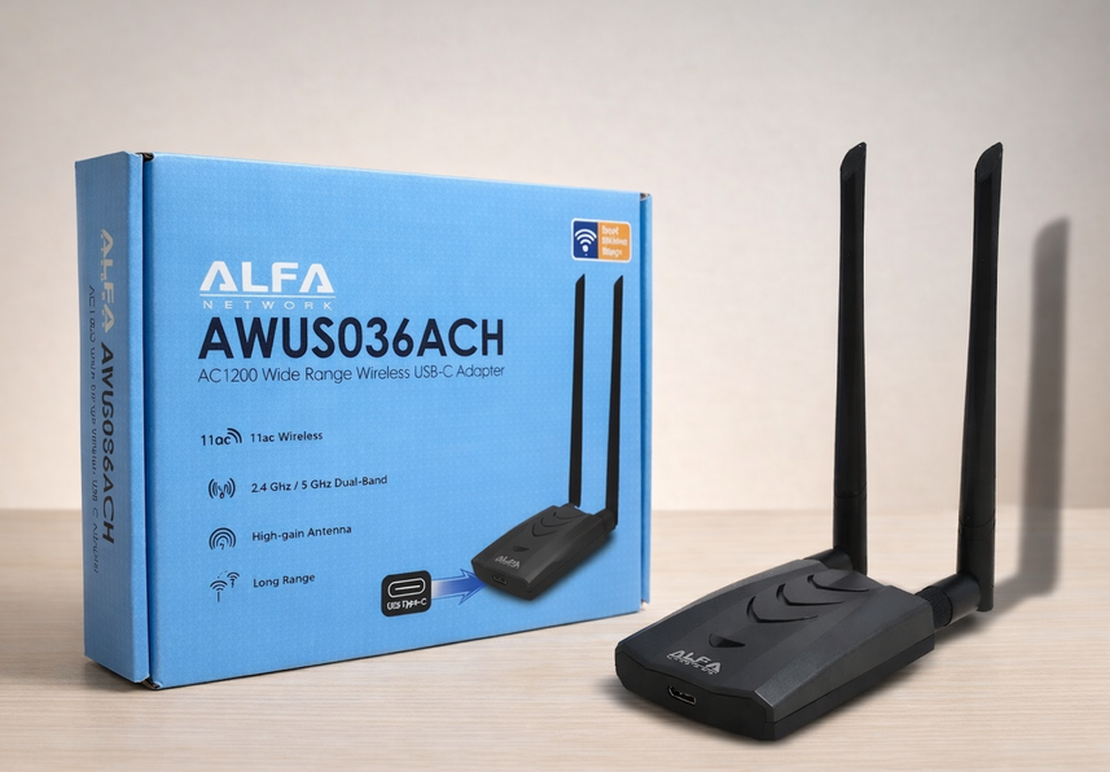

7. Alfa AWUS036ACH

Ever wondered how someone can sit in a car across the street and still maintain a connection to a building’s Wi-Fi? They’re usually not relying on the small, low-power adapter built into a laptop. In many setups, they use an external high-gain Wi-Fi adapter like an Alfa device.

The Alfa AWUS036ACH is a popular choice in wireless security testing. It’s a USB Wi-Fi adapter designed to work with external antennas, which can improve reception and transmission compared to many built-in laptop radios. In practice, that can mean detecting networks your laptop struggles to see and maintaining more stable links in challenging environments, including through walls and across longer distances.

How the Alfa Adapter Works: Packet Injection & Monitor Mode

1. Monitor Mode:

Most standard Wi-Fi adapters operate in a mode where they ignore traffic that isn’t meant for your device. Many Alfa adapters support switching into monitor mode, which disables that filtering so the adapter can capture wireless frames in the area for analysis.

In monitor mode, your laptop can observe management and data traffic on a channel, which is useful in authorized assessments for tasks like troubleshooting wireless issues, auditing encryption and handshake behavior, and detecting rogue access points.

2. Packet Injection: Forcing the Conversation

The Alfa adapter also supports Packet Injection, which means it can transmit crafted 802.11 frames rather than only passively listening. In authorized wireless audits, this capability is often used to test how a network behaves under common disruption scenarios and to validate whether security controls are configured correctly.

One example you’ll often hear discussed is forcing a client to reconnect so a tester can capture a WPA/WPA2 handshake (.cap file) for offline analysis. It’s important to stress that attempting to deauthenticate devices or capture handshakes on networks you don’t own or don’t have explicit permission to test is illegal and unethical in many jurisdictions.

Case Study: Wardriving Attacks on Retail Wi-Fi Networks (TJX Breach)

Between 2005 and 2007, attackers carried out one of the largest retail breaches of its era by targeting the Wi-Fi networks of TJX Companies, the parent company of TJ Maxx and Marshalls. Instead of attacking internal systems directly, they reportedly operated from nearby parking lots using wardriving techniques, scanning for weak wireless networks protected by outdated WEP encryption. While investigators did not publicly name the exact hardware, reports described the use of high-power external Wi-Fi gear capable of monitoring traffic and transmitting from a distance, similar to adapters commonly used in modern wireless security testing, such as the Alfa AWUS036ACH. The incident exposed more than 45 million payment card records and demonstrated that an attacker doesn’t need to step inside a building to compromise a poorly secured network 9.

8. O.M.G Cable

This is another popular device after Flipper Zero, and it’s a good reminder to be cautious with something most people treat as harmless: charging cables. The O.MG Cable, created by security researcher Mike Grover , looks like a standard Apple Lightning or USB-C cable. Inside the USB connector, it hides a tiny embedded board that can expose a lightweight web interface over Wi-Fi.

That’s what makes it so unsettling: cables are everywhere, and people rarely think twice before plugging one into a phone or laptop. In an adversarial scenario, a cable that behaves like more than “just power” can turn a routine charge into a security risk.

How the O.MG Cable Works:

1. The Invisible Internal Tech

Inside this tiny USB-C cable is a complete circuit board with a specialized chip that can create its own Wi-Fi hotspot. If the cable is connected to a target device, even “just for charging,” an attacker within range could connect to the cable’s Wi-Fi and access its control interface.

From the target’s perspective, the cable can present itself as an external accessory (for example, a keyboard-like HID device). From the attacker’s side, it can provide a remote control panel on a phone or laptop, which is why these cables are often discussed in the context of red teaming and security awareness.

2. The Mobile Command Center

An attacker doesn’t need to physically handle the phone. In a malicious scenario, they could open a browser on their own device, authenticate to the cable’s interface, and inject keystrokes remotely. Because the input is coming from a “trusted” accessory, it can sometimes slip past defenses that focus on files or apps, allowing an intruder to trigger scripted actions and potentially access sensitive information.

3. Self-Destruct & Stealth

The O.MG Cable also advertises features like Geofencing, which can restrict when the payload is active based on location (for example, only triggering in a specific area such as an office). Another notable feature is Self-Destruct: if the operator thinks the device might be discovered, they can send a command to wipe or disable its malicious functionality, effectively returning it to a “normal” charging cable and making analysis harder.

Case Study: The “Juice Jacking” Warning (FBI & FCC)

Avoid using free charging stations in airports, hotels or shopping centers. Bad actors have figured out ways to use public USB ports to introduce malware and monitoring software onto devices. Carry your own charger and USB cord and use an electrical outlet instead. pic.twitter.com/9T62SYen9T

— FBI Denver (@FBIDenver) April 6, 2023

While the O.MG Cable is a specific tool, it reflects a broader real-world concern behind the FBI’s 2023 “juice jacking” warning. In April 2023, the FBI’s Denver office advised travelers to avoid public charging stations after researchers demonstrated how malicious cables and compromised charging setups could be used to target users. In these demonstrations, attackers left cables that looked legitimate (but weren’t “just chargers”) at public stations. When a victim plugged in to charge, the cable delivered power while also enabling an attacker to interact with the device.

Even though the FBI did not call out the O.MG Cable by name, the warning highlights the underlying risk: when you blindly trust unfamiliar hardware, sensitive data can be exposed. The original FBI warning tweet is attached for your reference.

9. LAN Turtle

Another USB gadget, but with a very different purpose. The LAN Turtle looks like a simple USB-to-Ethernet adapter, the kind you’d use with a laptop or docking station. But appearances are deceptive: it’s a small Linux-based microcomputer designed for long-term network access in a controlled testing scenario.

Unlike tools that run a quick demo and are removed, the LAN Turtle is meant to stay connected and provide persistence. In the wrong hands, that persistence becomes a stealthy backdoor into an internal network.

How the LAN Turtle Works: Stealth and Persistence

1. The “Man-in-the-Middle” Connector

The LAN Turtle can be used for man-in-the-middle style testing. In a typical setup, you unplug the Ethernet cable from a computer, connect it to the Turtle, and then connect the Turtle to the computer’s USB port, as shown in the image. From the user’s perspective, nothing seems to change and the machine may continue to have network access.

Behind the scenes, the USB connection powers and manages the device while network traffic passes through its Ethernet interface. In an unauthorized scenario, that placement could allow an attacker to observe network activity and collect sensitive information. In an authorized assessment, it’s used to validate how much exposure exists on a local wired segment.

2. The Remote Backdoor (Reverse SSH)

In many environments, firewalls are designed to stop incoming connections. The LAN Turtle flips that model: once it’s on the inside, it can initiate an outbound connection to an external system controlled by the operator. Because the traffic originates from within the network, perimeter defenses may treat it as normal outbound activity and allow it through.

That can create a persistent, encrypted tunnel back into the organization’s internal network. In legitimate security testing, this is used to demonstrate why outbound filtering, network segmentation, and device control policies matter just as much as blocking inbound threats.

3. Automated Reconnaissance

Things get more dangerous once it’s in place. The LAN Turtle isn’t just “plugged in and idle” at a workstation, it can run continuously and automate internal reconnaissance. Over time, it may scan the local network to identify exposed services, weak devices, or poorly patched systems and then report those findings back to the operator.

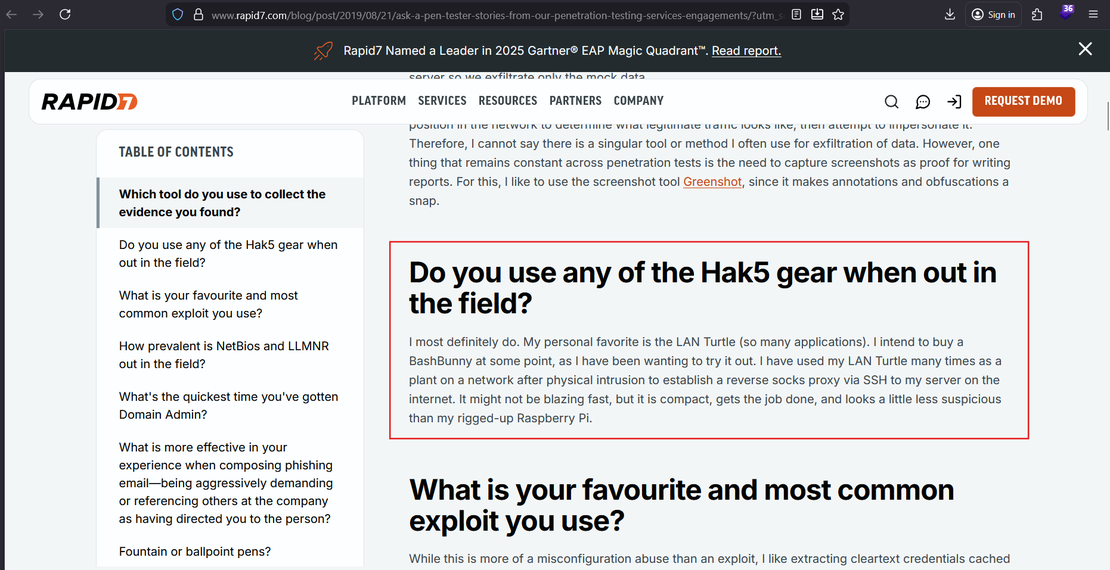

Real-World Use Case: Covert Network Implants in Corporate Offices

During authorized physical penetration tests, red teams have demonstrated how covert network implants like the LAN Turtle can be connected inside an office to gain internal network access. Once in place, the device can establish a reverse tunnel back to the operator, illustrating how “inside-the-LAN” footholds can bypass perimeter-focused defenses, especially in environments that allow unrestricted outbound connections. Firms such as Rapid7 and Mandiant have described engagements where devices in this class were used as part of real penetration testing work 10.

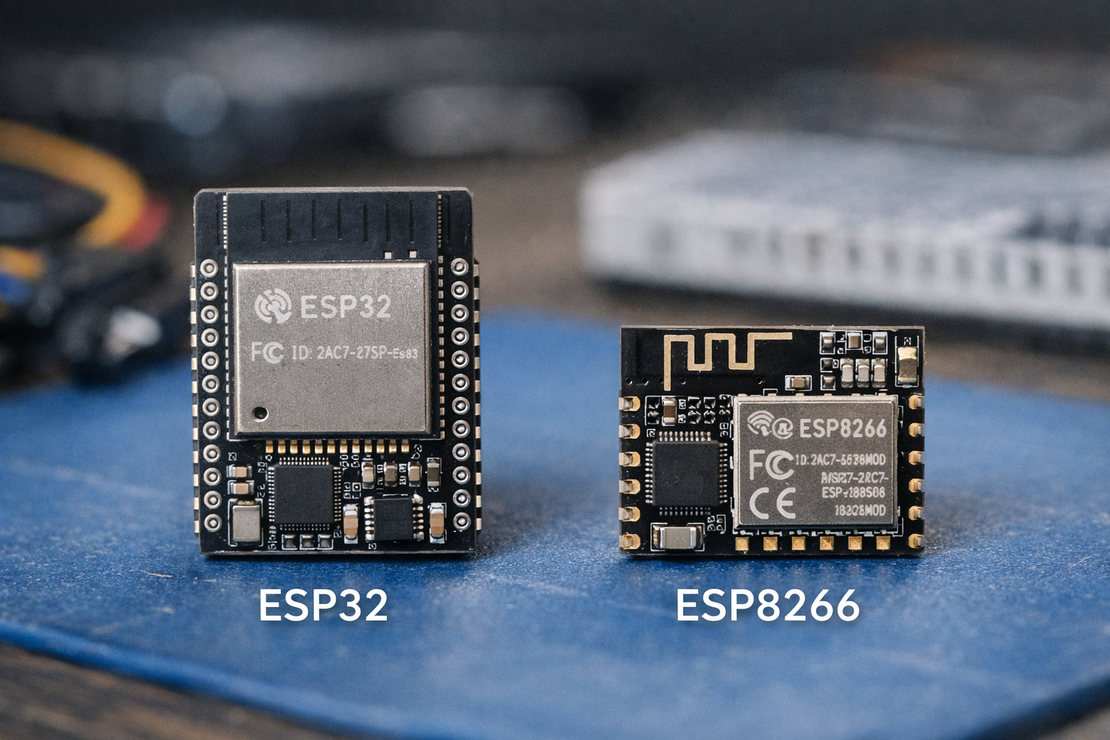

10. ESP32 / ESP8266

One of the most affordable options on this list is the ESP32 (and its predecessor, the ESP8266). These boards often cost around $5 and weren’t created for “hacking” at all. They’re widely used in consumer IoT products, powering things like smart light bulbs, sensors, and small embedded projects. But because they’re inexpensive, widely available, and include built-in Wi-Fi, they’ve also become popular in the security community for prototyping and wireless research.

How the ESP32/ESP8266 Works: The DIY Disruptor

1. The “Deauth” Wristwatch

With the right firmware, these $5 boards can be turned into a Wi-Fi disruption tool that demonstrates deauthentication-style attacks. One well-known example is the open source Spacehuhn Deauther. Unfortunately, devices like this are often used irresponsibly to knock nearby clients off Wi-Fi as a prank, because triggering disruptions can be as simple as pressing a button.

Technically, the idea relies on management-frame abuse: sending spoofed “disconnect” messages that force devices to drop and reconnect. In modern environments, it’s less effective against WPA3 networks and setups that use Protected Management Frames (PMF / 802.11w), which are specifically designed to make these attacks harder.

2. The Wi-Fi Honeypot (Beacon Spam)

In this image, you can see a common modern Wi-Fi security test scenario. A tiny ESP32 is broadcasting dozens of fake Wi-Fi network names that appear on a nearby smartphone, ranging from “Free Public WiFi” to “Skynet_Global.” These aren’t real routers. They’re simulated SSIDs generated by the ESP32 to see how users react when their device suddenly shows a tempting list of “available networks.”

The real risk here isn’t the chip itself, it’s human behavior. When people connect without verifying what the network actually is, they can be routed into a captive portal or other credential-harvesting trap. Depending on the setup, a malicious access point may also be able to observe or manipulate some traffic, especially if users ignore browser warnings and don’t use protections like HTTPS and VPNs.

USE CASE: ESP-Powered Wi-Fi Penetration Demonstration

ESP32 boards show that wireless security testing doesn’t always require expensive, specialized equipment. In public demonstrations, researchers have used battery-powered ESP32 setups with custom firmware to explore how Wi-Fi management traffic can be abused, including forcing reconnect behavior and validating whether a network resists common capture-and-analysis scenarios. The takeaway is simple: even a low-cost microcontroller can disrupt and probe poorly secured Wi-Fi deployments, which is exactly why modern defenses and proper configuration matter 11.

Where to Buy Legit Hacking Devices Safely

Trusted vendors

These devices are popular enough that the market is full of cheap clones, questionable resellers, and outright scams. To reduce the risk of buying nonfunctional gear, counterfeit hardware, or devices that have been tampered with, it’s best to purchase only from official manufacturers or authorized distributors. Here’s a list of trusted vendors.

Request Your Free 14-Day Trial

Submit a request to try Netlas free for 14 days with full access to all features.

Conclusion

In conclusion, modern attacks don’t always begin with malware. More and more, the weak point is the physical layer: signals, hardware, and the trust we extend to whatever we plug in or connect to. From USB devices that can present themselves as a keyboard, to Wi-Fi tools that imitate legitimate networks, to tiny microcontrollers that manipulate wireless traffic, some of today’s most impactful risks sit outside traditional software defenses.

Every device covered here maps to an attack path that has already been used in the real world, sometimes in authorized security testing, sometimes by nation-state operators, and sometimes by criminals.

Security today isn’t just about patching servers. It’s also about what happens when someone plugs something in, connects to the wrong Wi-Fi, or blindly trusts unfamiliar hardware. If you understand how these devices work and what risks they demonstrate, you’re already a step ahead of many real-world attacks.

Book Your Netlas Demo

Chat with our team to explore how the Netlas platform can support your security research and threat analysis.

Jumpcloud: “IoT Security Risks: Stats and Trends to Know in 2025”. ↩︎

MalwarebytesLabs: “Meet the entirely legal, iPhone-crashing device, the Flipper Zero: Lock and Code S04E25”. ↩︎

BeepingComputer: “FBI: Hackers use BadUSB to target defense firms with ransomware”. ↩︎

TheGuardian: “Visual guide: how Dutch intelligence thwarted a Russian hacking operation”. ↩︎

DigitalTrends: “It took them 15 years to hack a master key for 40,000 hotels. But they did it”. ↩︎

YouTube: “Proxmark 3 RDV2 Bypasses Millions of Hotel Rooms”. ↩︎

NewScientist: “Ships fooled in GPS spoofing attack suggest Russian cyberweapon”. ↩︎

Rapid7: “Ask a Pen Tester: Q&A with Rapid7 Penetration Tester Aaron Herndon”. ↩︎

Related Posts

September 12, 2025

Bug Bounty 101: Top 10 Reconnaissance Tools

June 10, 2025

How to Detect CVEs Using Nmap Vulnerability Scan Scripts

June 19, 2025

Nmap Cheat Sheet: Top 10 Scan Techiques

October 10, 2025

I Analysed Over 3 Million Exposed Databases Using Netlas

September 5, 2025

Mapping Dark Web Infrastructure

August 13, 2025

Bug Bounty 101: The Best Courses to Get Started in 2025